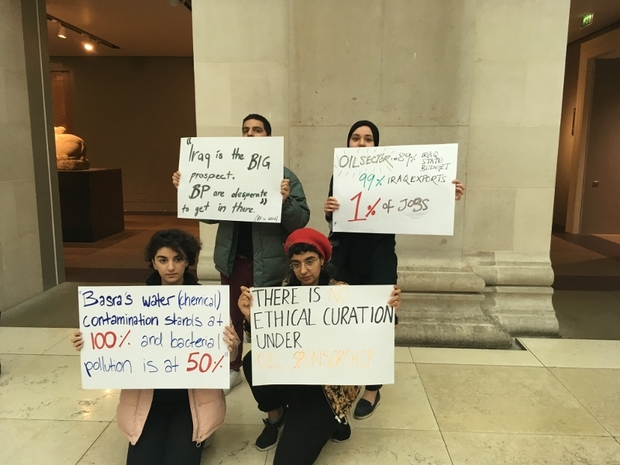

Iraqi and British activists protest BP’s sponsorship of Assyrian exhibition

Middle East Eye

7 November 2018

The British Museum’s latest show is a celebration of Iraqi culture. Why is an oil giant accused of exploiting Iraq sponsoring it, protesters ask.

British-Iraqis joined the anti-oil sponsorship group “BP or not BP?”; holding banners drawing attention to the company’s involvement in the planning of the Iraq war, the water contamination in Basra and the low number of Iraqis employed by an oil sector that dominates the country.

Middle East Eye reached out to BP for comment but the company did not immediately respond.

Some of the activists dressed up as BP and British Museum executives, handing out glasses of “oil” (water and food colouring) and standing in front of a mocked-up BP logo that read, “Making you history”.

“We want people to recognise the role the British Museum has in facilitating the theft of Iraqi objects, as well as the role it has in helping companies like Shell and BP whitewash their past and present in Iraq and around the world,” Mend Mariwany, a British-Iraqi activist who organises cultural events, told Middle East Eye.

The dubious colonial origin of many of the artistic treasures on display at the British Museum has long been a controversial subject.

And the continued commercial exchange of ancient artefacts continues to rankle the Iraqi authorities.

Just a few days ago, a 3,000-year-old Assyrian artefact was sold for $31m at Christie’s, in New York, in spite of last-minute protests by the Iraqi government.

‘Strategic interest’

“We haven’t forgiven or forgotten BP for their role in the invasion,” another British-Iraqi activist, who asked not to be named, said.

“This is supposed to be a celebration of Iraqi culture and it’s just the audacity of BP to sponsor it when they contribute and continue to contribute to so much destruction.”

Mariwany held a sign that read: “Iraq is the big oil prospect. BP is desperate to get in,” a truncated quote from the minutes of a meeting held in November 2002, four months before the invasion of Iraq, between the UK’s foreign office and BP.

“BP” executives enjoying a glass or two of oil (Kristian Buus)

“BP” executives enjoying a glass or two of oil (Kristian Buus)The oil company had been told that the UK government believed British firms should be rewarded with a share of Iraq’s vast oil and gas reserves as a return for then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s military commitment to American plans for regime change.

In public, BP said that it had no “strategic interest” in Iraq, but government documents later revealed that the oil company believed that Iraq was “more important than anything we’ve seen for a long time”, and that it was willing to take “big risks” to get a share of the world’s second-largest oil reserves.

This history is part of the reason why campaigners believe that BP should not be allowed to sponsor a landmark exhibition exploring the seventh century BC Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, who ruled his empire from Nineveh, now northern Iraq.

But the company’s present day activities in Iraq are just as pressing for the activists.

The United Nations says that while oil contributes 60 percent of Iraq’s GDP, 99 percent of its exports and over 90 percent of government revenue, the oil sector currently employs only 1 percent of the total labour force.

More than 90,000 people have been hospitalised in Basra due to seriously contaminated water, with industrial pollution from the oil industry a key contributor.

Banners advertising the new exhibition inside the museum (MEE/Oscar Rickett)

Banners advertising the new exhibition inside the museum (MEE/Oscar Rickett)Protests have swept across the country, particularly in oil-rich Basra, where the industry’s wealth has not trickled down to the people, who instead see only growing impoverishment and decaying services.

“BP brings in their own people. They do not train Iraqis. They do not contribute to the Iraqi economy”, Mariwany said.

“All they do is profit from it. They also use exhibitions like this to attract important Iraqi government officials and lobby them.”

BP claims otherwise, and in August 2015 said that 93 percent of the workforce at their Rumaila oil field was Iraqi nationals. Petroleum industries are known generally to not create many job opportunites.

Controversial climate

There is an ongoing battle in Britain over the sponsorship of cultural institutions by oil companies.

Climate change protesters have long argued that fossil fuel companies – particularly BP – gain invaluable PR from these sponsorships and that institutions that allow them to do this are complicit.

In 2016, BP announced it was ending its sponsorship of the Tate Britain, another public museum, after concerted pressure by activists. In the same year, BP’s sponsorship of the Edinburgh festival ended.

Yet the cash BP has provided to the institutions pales in comparison to other revenues.

When the oil giant pulled out of the Tate, it was revealed that the company had only provided £3.8 million in funding over a period of 17 years.

Figures revealed that between 2007 and 2011, BP provided less than 0.5 percent of Tate’s income.

Banners for the new exhibition seen outside the front of the British Museum (MEE/Oscar Rickett)

Banners for the new exhibition seen outside the front of the British Museum (MEE/Oscar Rickett)The figures are believed to be similar with the British Museum, with the multinational providing less than 0.5 percent of its budget.

Danny Chivers, of BP or not BP?, told MEE that what was striking was the way in which BP used its sponsorship of the British Museum to “put forward its own geopolitical interests”.

Among other examples, BP sponsored an event with the Mexican government at a time it was bidding for oil leases in Mexico and sponsored the Sunken Cities exhibition in partnership with the Egyptian government, where it has vast gas interests. Now, it is Iraq that is in the spotlight.

Looking at this pattern, Chivers says, “it just becomes obvious in whose interest these deals really are”.

Employees of the British Museum were not at liberty to discuss what they truly thought of BP’s sponsorship. “I don’t think,” one said.

“I’m just glad we live in a country where they can protest like this,” said another. “I’m not allowed to say what I think but I’m going to look into this. I’m interested.”

A 2016 survey by the Public and Commercial Services Union found that two-thirds of British Museum workers were supportive of the anti-BP protests.

A senior member of the museum’s management team would not comment, telling MEE he had a meeting to attend.

Throughout the controversy surrounding BP’s involvement in the British Museum, its spokespeople reiterate the institution’s gratitude to the company for its support, and claim that landmark exhibitions wouldn’t be possible without it.

The museum is free to enter for visitors but everywhere donation boxes encourage a suggested donation of £5. It is a public institution but a form of cultural privatisation is taking place: BP’s logo is everywhere.

‘I don’t care’

A group of primary school children waved and cheered on the activists.

A group of 16-year-olds on a school trip from St Albans, an affluent commuter town just north of London, said they hadn’t been aware of BP’s involvement in Iraq or of its sponsorship of museum exhibitions.

One said: “I don’t care about anything that doesn’t affect me, so I don’t care about this.”

He did offer an opinion on capitalism as a whole, however, which he pronounced “the best of all the systems”.

One of his friends disagreed with him and voiced support for the activists, saying that what had happened in Iraq wasn’t right and that BP should not be allowed to get away with what they were doing.

Outside the temporary home of Ashurbanipal, “King Of The World, King Of Assyria”, one of the activists draped herself in an Iraqi flag.

But it isn’t just Iraq at stake, Chivers said.

He pointed to the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which said that radical reductions in the amount of fossil fuel we use need to happen in the next 12 years to limit climate catastrophe.

As an anti-fossil fuel activist, news like that helps him get his message out into the public.

As for the British Museum, Chivers said, the idea that “it can’t find the money another way betrays a serious lack of imagination”.

*************************************************************

See more on this issue in a short video made by activists: