The Border Wetlands of Iran-Iraq: an Environmental Crisis with Regional Consequences

By Toon Bijnens, Save the Tigris Campaign

For years experts have warned of the destructive impact of Iran’s policies of river flow alterations on the southeastern provinces of Iraq. In 2012 the UK-based International Centre of Development Studies in a report argued the environmental effects will be huge, and even Iranian officials have warned of the impact the water crisis could have on the whole region. In fact the consequences are already visible in the Mesopotamian Marshlands, in the border area of Iran-Iraq.

Part of the Mesopotamian Marshlands, Hawizeh Marsh straddles the Iran-Iraq border, with 2/3 located in Iraq, called Hawizeh, and 1/3 in Iran, called Hoor al-Azim. Its main sources are the Tigris River on the Iraqi side and the Karkeh River on the Iranian side. Vast areas of Hoor al-Azim have been dried for oil exploration and desiccated due to oil drilling and upstream dam construction (Karkeh Dam). This has caused immense dust storms which reached the city of Ahwaz in Khuzestan last February, causing large protests. Considering it is one of the main causes of the dust storms, Iranian authorities recently decided to re-flood large parts of Hoor al-Azim. The revival of these wetlands is one of the priorities of the current Iranian government in order to counter the dust storms and horrendous air quality in the city of Ahwaz, which according to the World Health Organization is the most polluted city in the world. However, Hoor-al-Azim is far from restored. The head of the Iranian Department of Environment, Massoumeh Ebtekar, claimed last February that 80% of the wetlands have been re-filled and that it has become a “tourist destination”, but when one visits the site this is hardly the case. Considering its location on the Iran-Iraq border and the large number of oil installations, the area now has increased police presence and alertness of the authorities especially since the recent attacks in Tehran. This makes Hoor al-Azim not a place for unsuspicious bird-watchers, even if flamingos can be seen in these wetlands.

Dust storms have continued to reach the city of Ahwaz and other areas in Khuzestan province, as recent as June 2017. When I recently visited the city, the air quality was horrendous, coupled with extreme heat. At the end of June the temperature in the city reached 54 degrees Celcius, one of the hottest ever recorded on earth. This takes its toll on the local population, even if power outages are rare compared to the other side of the border in Iraq. But it demonstrates that to turn the tide towards environmental revival, in particular for Hoor al-Azim, is a long-term effort that requires sustainable measures. In the meantime, there are local environmentalists who advocate for environmental measures at city-level in Ahwaz. Young Ahwazis of all ethnic backgrounds have developed several initiatives to improve the situation in their city, and attempt to maintain a dialogue with the local city authorities to advocate for stronger environmental measures. In Rofayeh, a small village near Hoor al-Azim, a local activist has been trying to revive the local gazelle population. However, very few indigenous people still reside in Hoor al-Azim, which looks mostly desolated with just a few houses and some cattle around. About 90% of the indigenous people have left the wetlands, the activist says. Shadegan wetland in eastern Khuzestan, with a larger local Marsh Arab population, is in much better shape but suffers from pollution as well.

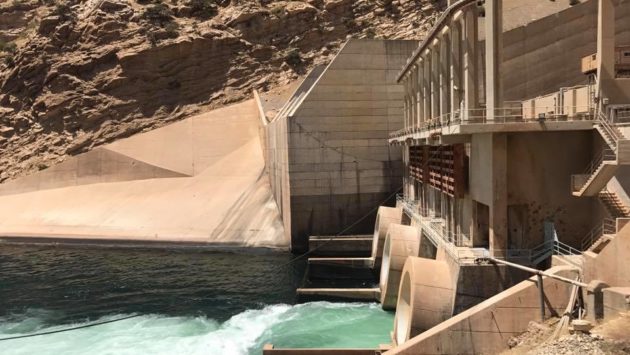

The environmental crisis that is going on here is of regional magnitude with the possibility of spillovers to Iraq. Desiccation in Iran further speeds up the process of climate change in the whole region, including Iraq, while social unrest due to environmental troubles could cause large numbers of environmental migration to neighbouring countries. Iraq is often weak as a downstream state vis-à-vis Iran and continues to suffer from its neighbour’s water policies: In recent years, Iran has stopped water flows in the Alvand River flowing to Iraq, the recently completed Daryan Dam will decrease water flows of the Sirwan River going to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and in addition, Sardasht Dam currently under construction in Iran will reduce the water supply in Iraqi-Kurdish border towns.

In Iraq, Hawizeh Marsh was historically the most stable marsh but has in the past decade experienced great water shortages. Construction of the Karkeh Dam in 2001 on the Karkeh River in Iran reduced Hawizeh Marsh flow on the south side where the marsh joins the Tigris River. Since 2009, the Marsh has been effectively split in 2 due to a 65km dyke on the Iran-Iraq border which was completed in 2009. According to Iran, the dyke was built in order to keep the water of Hoor al-Azim within Iranian borders to sustain the water levels on the Iranian side. This blockage has had a great negative impact on the habitat of the marsh as a whole as water cannot enter or exit freely anymore. There is hardly any water discharge to Iraq due to water shortages on the Iranian side. Decreased water levels have caused great salinity in the river waters of Basra and Maysan governorates. In addition, water close to the dyke is believed to be polluted due to oil industry installations and waste water in Hoor al-Azim, raising more concerns in Iraq.

When the Ahwar of Iraq, including Hawizeh Marsh, were inscribed in the World Heritage List in 2016, UNESCO set forth a list of recommendations, including for the state party of Iraq to “submit […] the map showing the boundaries according to the statement jointly signed with the State Party of the Islamic Republic of Iran”. Experts agree that in order to restore the water flows from Hoor al-Azim to Hawizeh Marshes the dyke should be removed and the Karkeh River should flow naturally. This is an issue that must be resolved through negotiations between both countries. Conservation of Hoor al-Azim and Hawizeh Marsh should be a joint project, and some Iranian officials in the past have even hinted of a joint restoration process. The Mesopotamian Wetlands are vital to all of Mesopotamia and should be regarded as a regional matter.

In an unexpected move, it has become more obvious that the sustainability of Hoor al-Azim, Hawizeh and the other marshes is a regional matter that involves several countries: Iranians have now turned to protest against Ilisu and other Turkish dams. An internet campaign – source unknown – has been launched against Turkish dam construction, claiming this is the main cause of the desertification of Hoor-al-Azim. Ebtekar, Head of the Department of Environment, on 16 June 2017 expressed that “Excessive construction of dams in Turkey has plunged Hoor-al-Azim wetlands into a dangerous condition”, calling on the Iranian Foreign Ministry to discuss the issue with Ankara in order to save the wetlands from desiccation. Ebtekar allegedly also blamed the desiccation of Iraq’s wetlands and the reduction of Iraq’s rivers water levels. Though it is obvious that it is mostly oil drilling methods within Iran that are to blame for the wetland’s condition, as government officials have on various occasions admitted. This can serve as a strong reminder for Iraq, where Majnoon oil field overlaps with the southern part of Hawizeh Marshes, of the negative consequences oil development has on the surrounding ecosystem. Nonetheless it is true that Turkish dam construction has had and continues to have a negative impact on the downstream Tigris River and the Mesopotamian Marshlands. The Iraqi government could regard this as an opportunity to ally with Iran and address with the Turkish government the construction of Ilisu and other Turkish dams. But such an action could hardly be taken seriously considering at the same time the Iraqi government does not address the disastrous impact of Iranian dams on its own country, the continued dam construction in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq or the continued threats by the Kurdistan Regional Government of cutting water flows to Southern Iraq. To seriously address the issue of Ilisu Dam would require to overturn the current regional paradigm of water use at the expense of others. This implies a change in domestic water policies of each country, and to subscribe instead to the idea that shared rivers, shared wetlands imply shared responsibility and require joint management.

To be continued.