We Call Upon the Kurdish Community to Take Urgent Action for Women’s Rights and Stand against Sexual Harassment

By Shahrazad Campaign, June 2016.

Executive Summary of a research on sexual harassment in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, produced by Al-Mesalla organization for Human Resource Development within the framework of Shahrazad Campaign, in cooperation with the Iraqi Civil Society Solidarity Initiative.

The study has been conducted by the local researcher Dr. Shino Khaleel.

Introduction

Sexual harassment is a social phenomenon which has a profound impact on Kurdistan communities. Women and girls are the vast majority of victims of sexual harassment, though studies indicate that other groups, such as adolescents, children and minorities may also be victims of harassment.

All too often, sexual harassment is misunderstood, and for this reason, it has remained a taboo subject, left unacknowledged and undiscussed. For a long time, people did not even use the term ‘sexual harassment’. However, this discomfort does not give us an excuse to ignore sexual harassment, nor can we pretend it does not exist: it occurs around us every day. We see it happen in our streets and our homes, yet its victims receive almost no recognition or help.

Sexually harassing women is a crime. It is not normal or acceptable, an event, to be ignored and avoided. It is also wrong to assume that the victim is responsible for his/her harassment; Sexual harassment is a serious violation and we cannot give any justification or excuse to the harasser.

Harassement is a choice taken by the harasser, and responsibility lies with him, regardless of the clothes the victim wears, the actions she takes, or where she is. Thus, we cannot in any way accept harassment as the result of a woman wearing the wrong clothes or being in the wrong place. The victim is very simply not responsible, neither fully nor partially.

The definition of sexual harassment

It is difficult to define sexual harassment, but this study attempts to identify some of its basic features. These include sexually affronting women without their acceptance, and any unwelcomed sexual advance which violates a woman’s body, privacy or feelings. Sexual harassment is any action or speech that makes a woman feel unsafe, uncomfortable or disrespected. Sexual harassment does not necessarily imply the actual act of sex, but includes the mere suggestion that sex is desired, and the accompanying pressure to consent.

Some may be confused about the difference between the concept of sexual harassment and courting in the street, but the two are entirely different.

Courting entails speaking words of admiration to another, offering a person one’s love or expressing a wish to marry. However it is conveyed, courting does not seek to humiliate and frighten the woman/girl. Sexual harassment, on the other hand, is a violent act against women, which stems from a sexual urge, and sometimes a motivation and desire to humiliate another person. Insulting and degrading the victim — as often happens in cases of sexual harassment — can have the perverse effect of legitimizing the act itself. This is because the victim, once shamed, is taken to be at fault and is made to seem responsible. Because of this, sexual harassment has become politically and culturally accepted in some communities.

Sexual harassment usually happens between women and men in positions of power, for instance, between a teacher and a student, a doctor and a patient, between a shop owner and a customer, or between a manager and his employee. Sexual harassment sometimes even occurs within a religious context, from a cleric.

Harassment can happen on the street, at the market and on public transportation, within government departments, in schools and universities, at work and in places of worship, during a medical visit, and at home. It can also occur through various forms of communication, such as on the phone or over the internet.

Wherever and however it happens, sexual harassment increases women’s suffering. Women seeking to advance their education or move ahead in their careers are held back, literally and psychologically, because of harassment which goes unnoticed. Moreover, all too often, harassers do not differentiate between girls and women, between those who are underage and those who are married with families of their own.

Studying sexual harassment is the first step to understanding the phenomenon, and to think of the ways to stop it

Given the fact that the sexual harassment of women is a thorny and sensitive issue, this study aimed to focus and clarify this phenomenon in a particular area: the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It sought to define its various forms and identify the most common places it was found to occur. The goal was to establish some of the primary causes of sexual harassment, and to develop concrete social and legal processes that might effectively deal with it: that is, legislation dedicated to addressing the issue of sexual harassment directly so that it might mitigate its impact on our streets and in our schools, at our markets and work places.

The researcher, Dr. Shino Khaleel, conducted a study, which took a random sample of 205 women and girls (representing the most important cities of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq), 57 from the city of Dohuk, 65 from the city of Sulaymaniyah, and 83 from the city of Erbil. The study was conducted during the first half of 2015.

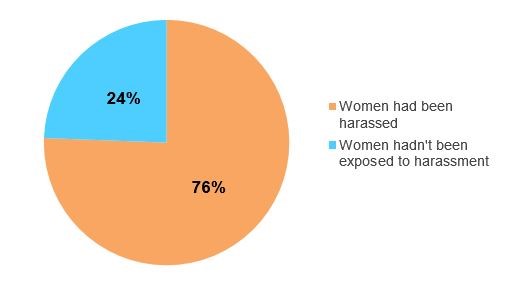

75.6% of the sample stated that they had been harassed, while the rest, 24.4%, claimed not to have been exposed to it. This data clearly confirms that the sexual harassments of women is a widespread phenomenon in the Kurdish community. However, this is not surprising because the Kurdish community is traditionally a patriarchal society, in which inherited customs and traditions are still very much alive in today’s practices. This includes the idea that women are inherently inferior to men, and that should a woman lack appropriate modesty, this is reason to harass her.

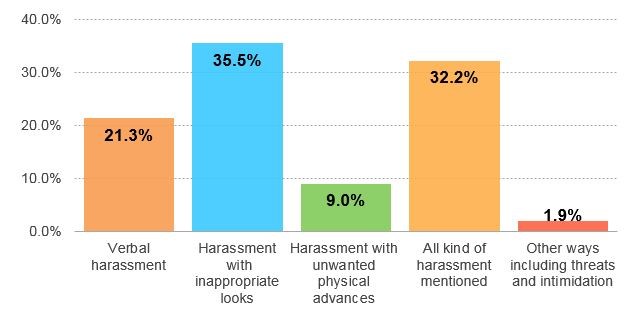

As for the types of harassment suffered by respondents, the study showed:

- 21.3% have been subjected to verbal harassment

- 35.5% have been subjected to leers and inappropriate looks

- 9% confirmed being subjected to unwanted physical advances.

- 32.2 % experienced each kind of harassment mentioned above

- 1.9% have been harassed in other ways, including threats and intimidation, as well as harassment over the telephone and on the internet.

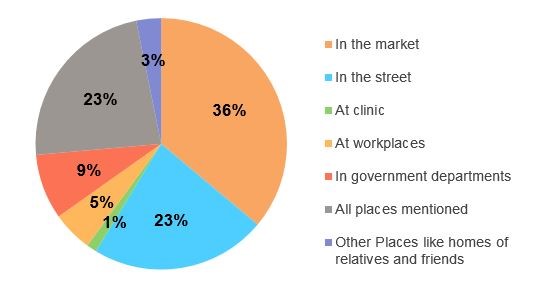

The data referring to places where sexual harassment took place revealed that:

- 36.1% reported being harassed in the market

- 22.6% in the street

- 1.3% at a clinic

- 5.2% at their workplaces

- 8.4% in government departments

- 23.2% confirmed having been subjected to harassment in more than one of these places

- 3.2% reported being harassed at places other than those mentioned, like the homes of relatives and friends.

The ways victims tend to deal with the harasser/harassment can be described by the following figures:

- 76.1% answered that they preferred to remain silent and avoid the harasser

- 23.9% rejected the harassment, confronted the harasser and exposed him.

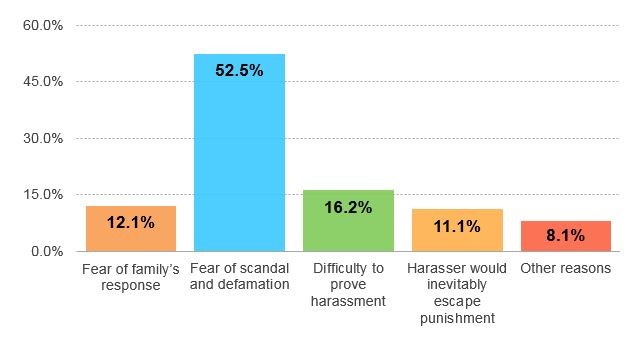

48.3% chose not to file a lawsuit against the harasser (and 12.1% confirmed that the reason for taking no legal action was fear of their family’s response, while 52.5% claimed a fear of scandal and defamation. Another 16.2% replied that it was simply too difficult to prove the crime of harassment, and 11.1% asserted that the harasser would inevitably escape punishment. In addition, 8.1% stated other reasons (e.g., the perceived banality of the subject, lack of interest in the matter).

As to the respondent’s awareness of laws relating to sexual harassment:

- 25.9% confirmed that they were aware of and knowledgeable about laws that criminalize harassment

- 74.1% asserted they were unaware of these laws

These results yield some important conclusions about the legal side of harassment: first, they make evident the weakness of laws that criminalize harassment, and second, citizens and law enforcement officers tend to avoid any legal interference in harassment cases as they are sensitive issues that might spark a tribal differences and conflicts, including the payment of compensations and other means of extortion. This kind of corruption occurs due to the absence of the rule of law in the Kurdish community in particular, and in Iraqi society more generally.

Is a woman’s appearance or whereabouts relevant to charges of harassment?

Even in the sample of this study there emerged two distinct opinions about a woman’s appearance and way of dressing, and its relationship to harassment. First, respondents confirmed that men have no right to harass a woman if she is wearing something that attracts him — the freedom to dress as one wishes is a part of a woman’s personal freedom, and no one has the right to violate her body just because she wears something which makes her attractive. The researcher recalls that Iraqi women in the seventies had more freedom in choice of clothes than they do now.

The research suggests that the lower rates of harassment found in the seventies indicates that an individual who chose to harass was shunned by his community, and so was afraid of the reaction of the society around him, which actively renounced harassment. This suggests that the harassment we see today is the result of an imbalance in the value system of the society as a whole, and of the harasser in particular.

The second view that emerged from the study sees the responsibility for the harassment of women as a shared one. A woman may, through her choice of clothing, encourage men to molest her. She is thus free to the extent that she does not ‘infringe’ on the freedom of others. Because a woman’s clothes might provoke the desire of a man who cannot by his very nature, control in his sexual desires, the wrong choice of clothing might be said actually to compel him to harass. This attitude is prevalent in the eastern community, which again, is more conservative and traditional.

The study also showed that 56.6% of those questioned said that the presence of women in crowded and enclosed spaces may give the harasser more opportunities for harassment, while 43.4 % of respondents disagreed that the place where the victim was might be the reason for harassment. The study showed that 54.1% of the respondents believe that staying late outside the home increases one’s chances of being harassed. In contrast, 45.9% rejected the idea that this might be a reason for the harassment.

The impact of sexual harassment on women’s psychological, economic and social well-being

The study confirms that the impact of sexual harassment are primarily psychological:

74.6% said that harassment psychologically affected them

15.6% said that harassment may have had adverse economic consequences (which is to be expected because sexual harassment on the job often prevents women from working at all).

9.8% claimed that the damages they suffered were social in nature, in the form of negative and critical responses from family and the community.

Customs and tradition as reasons for the general silence on the issue of harassment, and in turn, as causes of its rise

62% of respondents said that the community itself contributed to the spread and persistence of sexual harassment. This is due to the fact that the Kurdish community is a traditional one, governed predominantly by norms and laws which rule through prohibiting and forbidding certain actions, rather than protecting rights. This is often what drives women to keep silent in cases of harassment: the fear that they will be blamed by society and held accountable.

The study showed that 77.6% of the sample asserted that their silence may be the reason for their continued vulnerability to exploitation and abuse. This in turn serves to make their harassers ever more persistent. The perpetrator of harassment — the man — is always in a position of strength, and any woman who dares to complain, or take recourse to the law is often subjected to further harassment by the police. The victim is thus afraid of being accused by the police themselves of doing something wrong, a distortion of the truth which could hurt not only her, but the reputation of her family.

Recommandations: Addressing the phenomenon of the harassment of women is a complex problem, one which requires a large and focused effort by many agencies, both governmental and non-governmental, along with educational institutions and individual families. Below are the most important recommendations that emerged from the study:

Recommandations for the government :

- Development of legislation to ensure a clear and explicit stand against sexual harassment and an aim to reduce it and toughen sanctions against the perpetrators.

- Training for police in terms of how to deal with sexual harassment cases, and an intensification of security for and in support of victims.

- Establishment of special offices to receive complaints of sexual harassment, staffed with trained women and men to deal with these cases.

- Review and reform of school curricula to emphasize equality in all public places, including markets, streets and entertainment venues. Emphasis on educating the younger generations about harassment and the importance of respecting the personal space of others.

Recommandations for all different types of civil society organizations’ activities

- We call on civil society organizations to implement programs and activities aimed at raising the legal and social awareness for all segments of society, especially women, highlighting the fact that harassment is a crime and is thus forbidden. Women should be encouraged to file a lawsuit in the case of any harassment so that the harasser is identified. Communities should ensure support for the victim.

- We call on the youth to open dialogues through social networking sites to raise awareness of and alert people to the risks of sexual harassment (for perpetrator and victim alike), to encourage conversations between young people of both sexes as an alternative to violence and inequality, and to build a civilized society governed by principles of justice, gender equality and respect for others’ values.

- We call on university professors, journalists, actors, artists and tribal leaders, clerics and members of parliament, each according to his/her abilities and capabilities, to continue to perform the role of nurturing a culture of equality, and an awareness that the public places are intended to be used by both sexes.

- We call on families to encourage an interest in sex education within the family itself, and to encourage young people to discuss ways to protect themselves, and to respect the freedom of others, and to promote the values of equality between the sexes.