An education in occupation

An education in occupation

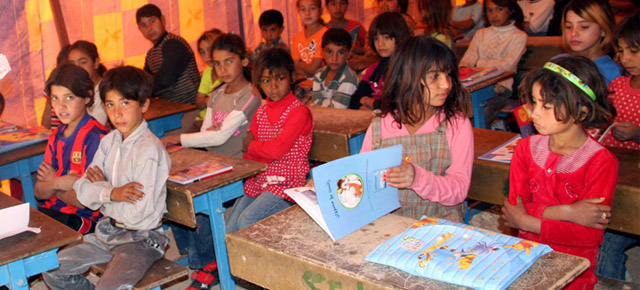

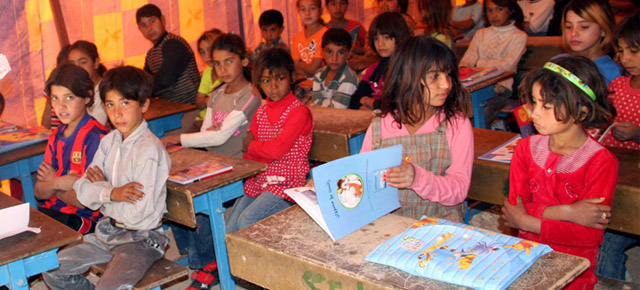

As the last American soldiers left Iraq in December, so, too, did many of the journalists who had covered the war, leaving little in the way of media coverage of post-war Iraq. While there were some notable exceptions — including two fine articles by MIT’s John Tirman that asked how many Iraqis had been killed as a result of the US invasion — overall the American press published few articles on the effects of the occupation, especially the consequences for Iraqis. As a college professor, I have a special interest in what happened to Iraqi universities under US occupation. The story is not pretty. Until the 1990s, Iraq had perhaps the best university system in the Middle East. Saddam Hussein’s regime used oil revenues to underwrite free tuition for Iraqi university students — churning out doctors, scientists, and engineers who joined the country’s burgeoning middle class and anchored development. Although political dissent was strictly off-limits, Iraqi universities were professional, secular institutions that were open to the West, and spaces where male and female, Sunni and Shia mingled. Also the schools pushed hard to educatewomen PDF, who constituted 30 percent of Iraqi university faculties by 1991. (This is, incidentally, better than Princeton was doing as late as 2009.) With a reputation for excellence, Iraqi universities attracted many students from surrounding countries — the same countries that are now sheltering the thousands of Iraqi professors who have fled US-occupied Iraq. Iraqi universities began their decline in the 12 years after the 1991 Gulf War. As the international sanctions regime cut off journal subscriptions and equipment purchases, academic salaries fell precipitously, and 10,000 Iraqi professors left the country. Those faculty who remained were increasingly closed off from new developments in their fields. In 2003, after the invasion, many Iraqi professors hoped that their university system would be revitalized under US occupation. They expected funding to buy new books, to replace equipment, and to repair the damage inflicted by the sanctions. And they hoped for new tolerance for open debate and inquiry. In fact, the opposite happened. It started during the chaos following the invasion. While American troops guarded the Ministries of Oil and the Interior but ignored cultural heritage sites, looters ransacked the universities. For example, the entire library collections at the University of Baghdad’s College of Arts and at the University of Basra were destroyed. The Washington Post‘s Rajiv Chandresekara described the scene at Mustansiriya University in 2003: “By April 12, the campus of yellow-brick buildings and grassy courtyards was stripped of its books, computers, lab equipment and desks. Even electrical wiring was pulled from the walls. What was not stolen was set ablaze, sending dark smoke billowing over the capital that day.” At the same time, the United States stripped Iraq’s universities of their leadership. In hisfirst executive order PDF as the new head of the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq, Paul Bremer removed members of the Ba’ath Party from senior management positions at all public institutions. Since one had to join the Ba’ath Party — whether one truly supported the party or not — in order to get ahead in Hussein’s Iraq, this order had the effect of removing most of Iraq’s senior university administrators and professors overnight. In thewords of journalist Christina Asquith, after this purge, “half of the intellectual leadership in academia was gone.” Control over Iraq’s universities now lay in the hands of Andrew Erdmann, a 36-year-old American, well-connected in Republican Party patronage networks, who was senior adviser to Iraq’s Ministry of Education. Erdmann spoke no Arabic and had no experience in university administration. In September 2003, Erdmann was succeeded by John Agresto, the former president of St. Johns College in New Mexico and a conservative opponent of multicultural education in the US culture wars of the 1980s. Agresto was picked to run the Iraqi university system because he was friends with Lynne Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. He too spoke no Arabic and, when the Post‘s Chandresekaran asked what he had read to prepare for his assignment, Iraq’s new top educator said he decided to read no books at all about Iraq — so he would have an “open mind.” Agresto estimated that it would cost $1.2 billion to rebuild Iraq’s 22 major universities and 43 technical institutes and colleges. Given that the US Congress appropriated over $90 billion for reconstruction and counterinsurgency in Iraq for 2004, this was not a large amount, and it was significantly less than the $2 billion that the United Nations and the World Bank had estimated would be the minimum necessary. (To give some sense of scale, $1.2 billion is the same as North Carolina State University’s annual budget.) But Congress only appropriated $8 million — less than 1 percent of what Agresto requested. In other words, Congress told Iraqi universities they were on their own. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) did set aside $25 million to help revitalize Iraqi universities — but the money went to American universities to do curriculum development. For example, USAID gave the State University of New York at Stony Brook $4 million (half the amount Congress appropriated to restore the entire Iraqi university system) to develop a new archaeology curriculum on behalf of four Iraqi universities. By 2004, looted, impoverished, and stripped of their intellectual and administrative leadership, Iraqi universities nevertheless embodied one of the last spaces — in a country increasingly engulfed by sectarian tensions — where people of different creeds could gather together. However, the principled commitment of many in university communities to cosmopolitanism and interfaith tolerance made the universities themselves targets for sectarian extremists and fundamentalists. Armed militias threatened women who did not cover themselves and intimidated professors who said things they did not like. According toThe Washington Times, 280 Iraqi professors were killed and another 3,250 fled the country by the end of 2006. Those assassinated included Muhammad al-Rawi, the president of Baghdad University; Isam al-Rawi, a geology professor who was compiling statistics on assassinated Iraqi academics when he himself was killed; and Amal Maamlaji, a Shia information-technology professor and women’s rights advocate at a predominantly Sunni university, who was killed with 163 bullets. Those faculty fortunate enough to move abroad became part of the great middle-class exodus from Iraq under US occupation. It is estimated that 10 percent of Iraq’s population, and 30 percent of its professors, doctors, and engineers, left for neighboring countries between 2003 and 2007 — the largest Arab refugee displacement since the Palestinian flight from the holy lands decades earlier. In just 20 years, then, the Iraqi university system went from being among the best in the Middle East to one of the worst. This extraordinary act of institutional destruction was largely accomplished by American leaders who told us that the US invasion of Iraq would bring modernity, development, and women’s rights. Instead, as political scientist Mark Duffield has observed, it has partly de-modernized that country. In the words of John Tirman, America’s failure to acknowledge the suffering that occupation wreaked in Iraq “is a moral failing as well as a strategic blunder.” Iraq represents a blind spot in our national conversation, one that impedes the cultural growth that stems from a painful recognition of error; and it hobbles the rational evaluation of foreign intervention. Is it too late to look in the mirror?

Hugh Gusterson

professor of anthropology and sociology at George Mason University, USA.

Article first published here: http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/hugh-gusterson/education-occupation

An education in occupation

As the last American soldiers left Iraq in December, so, too, did many of the journalists who had covered the war, leaving little in the way of media coverage of post-war Iraq. While there were some notable exceptions — including two fine articles by MIT’s John Tirman that asked how many Iraqis had been killed as a result of the US invasion — overall the American press published few articles on the effects of the occupation, especially the consequences for Iraqis. As a college professor, I have a special interest in what happened to Iraqi universities under US occupation. The story is not pretty. Until the 1990s, Iraq had perhaps the best university system in the Middle East. Saddam Hussein’s regime used oil revenues to underwrite free tuition for Iraqi university students — churning out doctors, scientists, and engineers who joined the country’s burgeoning middle class and anchored development. Although political dissent was strictly off-limits, Iraqi universities were professional, secular institutions that were open to the West, and spaces where male and female, Sunni and Shia mingled. Also the schools pushed hard to educatewomen PDF, who constituted 30 percent of Iraqi university faculties by 1991. (This is, incidentally, better than Princeton was doing as late as 2009.) With a reputation for excellence, Iraqi universities attracted many students from surrounding countries — the same countries that are now sheltering the thousands of Iraqi professors who have fled US-occupied Iraq. Iraqi universities began their decline in the 12 years after the 1991 Gulf War. As the international sanctions regime cut off journal subscriptions and equipment purchases, academic salaries fell precipitously, and 10,000 Iraqi professors left the country. Those faculty who remained were increasingly closed off from new developments in their fields. In 2003, after the invasion, many Iraqi professors hoped that their university system would be revitalized under US occupation. They expected funding to buy new books, to replace equipment, and to repair the damage inflicted by the sanctions. And they hoped for new tolerance for open debate and inquiry. In fact, the opposite happened. It started during the chaos following the invasion. While American troops guarded the Ministries of Oil and the Interior but ignored cultural heritage sites, looters ransacked the universities. For example, the entire library collections at the University of Baghdad’s College of Arts and at the University of Basra were destroyed. The Washington Post‘s Rajiv Chandresekara described the scene at Mustansiriya University in 2003: “By April 12, the campus of yellow-brick buildings and grassy courtyards was stripped of its books, computers, lab equipment and desks. Even electrical wiring was pulled from the walls. What was not stolen was set ablaze, sending dark smoke billowing over the capital that day.” At the same time, the United States stripped Iraq’s universities of their leadership. In hisfirst executive order PDF as the new head of the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq, Paul Bremer removed members of the Ba’ath Party from senior management positions at all public institutions. Since one had to join the Ba’ath Party — whether one truly supported the party or not — in order to get ahead in Hussein’s Iraq, this order had the effect of removing most of Iraq’s senior university administrators and professors overnight. In thewords of journalist Christina Asquith, after this purge, “half of the intellectual leadership in academia was gone.” Control over Iraq’s universities now lay in the hands of Andrew Erdmann, a 36-year-old American, well-connected in Republican Party patronage networks, who was senior adviser to Iraq’s Ministry of Education. Erdmann spoke no Arabic and had no experience in university administration. In September 2003, Erdmann was succeeded by John Agresto, the former president of St. Johns College in New Mexico and a conservative opponent of multicultural education in the US culture wars of the 1980s. Agresto was picked to run the Iraqi university system because he was friends with Lynne Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. He too spoke no Arabic and, when the Post‘s Chandresekaran asked what he had read to prepare for his assignment, Iraq’s new top educator said he decided to read no books at all about Iraq — so he would have an “open mind.” Agresto estimated that it would cost $1.2 billion to rebuild Iraq’s 22 major universities and 43 technical institutes and colleges. Given that the US Congress appropriated over $90 billion for reconstruction and counterinsurgency in Iraq for 2004, this was not a large amount, and it was significantly less than the $2 billion that the United Nations and the World Bank had estimated would be the minimum necessary. (To give some sense of scale, $1.2 billion is the same as North Carolina State University’s annual budget.) But Congress only appropriated $8 million — less than 1 percent of what Agresto requested. In other words, Congress told Iraqi universities they were on their own. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) did set aside $25 million to help revitalize Iraqi universities — but the money went to American universities to do curriculum development. For example, USAID gave the State University of New York at Stony Brook $4 million (half the amount Congress appropriated to restore the entire Iraqi university system) to develop a new archaeology curriculum on behalf of four Iraqi universities. By 2004, looted, impoverished, and stripped of their intellectual and administrative leadership, Iraqi universities nevertheless embodied one of the last spaces — in a country increasingly engulfed by sectarian tensions — where people of different creeds could gather together. However, the principled commitment of many in university communities to cosmopolitanism and interfaith tolerance made the universities themselves targets for sectarian extremists and fundamentalists. Armed militias threatened women who did not cover themselves and intimidated professors who said things they did not like. According toThe Washington Times, 280 Iraqi professors were killed and another 3,250 fled the country by the end of 2006. Those assassinated included Muhammad al-Rawi, the president of Baghdad University; Isam al-Rawi, a geology professor who was compiling statistics on assassinated Iraqi academics when he himself was killed; and Amal Maamlaji, a Shia information-technology professor and women’s rights advocate at a predominantly Sunni university, who was killed with 163 bullets. Those faculty fortunate enough to move abroad became part of the great middle-class exodus from Iraq under US occupation. It is estimated that 10 percent of Iraq’s population, and 30 percent of its professors, doctors, and engineers, left for neighboring countries between 2003 and 2007 — the largest Arab refugee displacement since the Palestinian flight from the holy lands decades earlier. In just 20 years, then, the Iraqi university system went from being among the best in the Middle East to one of the worst. This extraordinary act of institutional destruction was largely accomplished by American leaders who told us that the US invasion of Iraq would bring modernity, development, and women’s rights. Instead, as political scientist Mark Duffield has observed, it has partly de-modernized that country. In the words of John Tirman, America’s failure to acknowledge the suffering that occupation wreaked in Iraq “is a moral failing as well as a strategic blunder.” Iraq represents a blind spot in our national conversation, one that impedes the cultural growth that stems from a painful recognition of error; and it hobbles the rational evaluation of foreign intervention. Is it too late to look in the mirror?

Hugh Gusterson

professor of anthropology and sociology at George Mason University, USA.

Article first published here: http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/hugh-gusterson/education-occupation

An education in occupation

As the last American soldiers left Iraq in December, so, too, did many of the journalists who had covered the war, leaving little in the way of media coverage of post-war Iraq. While there were some notable exceptions — including two fine articles by MIT’s John Tirman that asked how many Iraqis had been killed as a result of the US invasion — overall the American press published few articles on the effects of the occupation, especially the consequences for Iraqis. As a college professor, I have a special interest in what happened to Iraqi universities under US occupation. The story is not pretty. Until the 1990s, Iraq had perhaps the best university system in the Middle East. Saddam Hussein’s regime used oil revenues to underwrite free tuition for Iraqi university students — churning out doctors, scientists, and engineers who joined the country’s burgeoning middle class and anchored development. Although political dissent was strictly off-limits, Iraqi universities were professional, secular institutions that were open to the West, and spaces where male and female, Sunni and Shia mingled. Also the schools pushed hard to educatewomen PDF, who constituted 30 percent of Iraqi university faculties by 1991. (This is, incidentally, better than Princeton was doing as late as 2009.) With a reputation for excellence, Iraqi universities attracted many students from surrounding countries — the same countries that are now sheltering the thousands of Iraqi professors who have fled US-occupied Iraq. Iraqi universities began their decline in the 12 years after the 1991 Gulf War. As the international sanctions regime cut off journal subscriptions and equipment purchases, academic salaries fell precipitously, and 10,000 Iraqi professors left the country. Those faculty who remained were increasingly closed off from new developments in their fields. In 2003, after the invasion, many Iraqi professors hoped that their university system would be revitalized under US occupation. They expected funding to buy new books, to replace equipment, and to repair the damage inflicted by the sanctions. And they hoped for new tolerance for open debate and inquiry. In fact, the opposite happened. It started during the chaos following the invasion. While American troops guarded the Ministries of Oil and the Interior but ignored cultural heritage sites, looters ransacked the universities. For example, the entire library collections at the University of Baghdad’s College of Arts and at the University of Basra were destroyed. The Washington Post‘s Rajiv Chandresekara described the scene at Mustansiriya University in 2003: “By April 12, the campus of yellow-brick buildings and grassy courtyards was stripped of its books, computers, lab equipment and desks. Even electrical wiring was pulled from the walls. What was not stolen was set ablaze, sending dark smoke billowing over the capital that day.” At the same time, the United States stripped Iraq’s universities of their leadership. In hisfirst executive order PDF as the new head of the Coalition Provisional Authority of Iraq, Paul Bremer removed members of the Ba’ath Party from senior management positions at all public institutions. Since one had to join the Ba’ath Party — whether one truly supported the party or not — in order to get ahead in Hussein’s Iraq, this order had the effect of removing most of Iraq’s senior university administrators and professors overnight. In thewords of journalist Christina Asquith, after this purge, “half of the intellectual leadership in academia was gone.” Control over Iraq’s universities now lay in the hands of Andrew Erdmann, a 36-year-old American, well-connected in Republican Party patronage networks, who was senior adviser to Iraq’s Ministry of Education. Erdmann spoke no Arabic and had no experience in university administration. In September 2003, Erdmann was succeeded by John Agresto, the former president of St. Johns College in New Mexico and a conservative opponent of multicultural education in the US culture wars of the 1980s. Agresto was picked to run the Iraqi university system because he was friends with Lynne Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld. He too spoke no Arabic and, when the Post‘s Chandresekaran asked what he had read to prepare for his assignment, Iraq’s new top educator said he decided to read no books at all about Iraq — so he would have an “open mind.” Agresto estimated that it would cost $1.2 billion to rebuild Iraq’s 22 major universities and 43 technical institutes and colleges. Given that the US Congress appropriated over $90 billion for reconstruction and counterinsurgency in Iraq for 2004, this was not a large amount, and it was significantly less than the $2 billion that the United Nations and the World Bank had estimated would be the minimum necessary. (To give some sense of scale, $1.2 billion is the same as North Carolina State University’s annual budget.) But Congress only appropriated $8 million — less than 1 percent of what Agresto requested. In other words, Congress told Iraqi universities they were on their own. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) did set aside $25 million to help revitalize Iraqi universities — but the money went to American universities to do curriculum development. For example, USAID gave the State University of New York at Stony Brook $4 million (half the amount Congress appropriated to restore the entire Iraqi university system) to develop a new archaeology curriculum on behalf of four Iraqi universities. By 2004, looted, impoverished, and stripped of their intellectual and administrative leadership, Iraqi universities nevertheless embodied one of the last spaces — in a country increasingly engulfed by sectarian tensions — where people of different creeds could gather together. However, the principled commitment of many in university communities to cosmopolitanism and interfaith tolerance made the universities themselves targets for sectarian extremists and fundamentalists. Armed militias threatened women who did not cover themselves and intimidated professors who said things they did not like. According toThe Washington Times, 280 Iraqi professors were killed and another 3,250 fled the country by the end of 2006. Those assassinated included Muhammad al-Rawi, the president of Baghdad University; Isam al-Rawi, a geology professor who was compiling statistics on assassinated Iraqi academics when he himself was killed; and Amal Maamlaji, a Shia information-technology professor and women’s rights advocate at a predominantly Sunni university, who was killed with 163 bullets. Those faculty fortunate enough to move abroad became part of the great middle-class exodus from Iraq under US occupation. It is estimated that 10 percent of Iraq’s population, and 30 percent of its professors, doctors, and engineers, left for neighboring countries between 2003 and 2007 — the largest Arab refugee displacement since the Palestinian flight from the holy lands decades earlier. In just 20 years, then, the Iraqi university system went from being among the best in the Middle East to one of the worst. This extraordinary act of institutional destruction was largely accomplished by American leaders who told us that the US invasion of Iraq would bring modernity, development, and women’s rights. Instead, as political scientist Mark Duffield has observed, it has partly de-modernized that country. In the words of John Tirman, America’s failure to acknowledge the suffering that occupation wreaked in Iraq “is a moral failing as well as a strategic blunder.” Iraq represents a blind spot in our national conversation, one that impedes the cultural growth that stems from a painful recognition of error; and it hobbles the rational evaluation of foreign intervention. Is it too late to look in the mirror?

Hugh Gusterson

professor of anthropology and sociology at George Mason University, USA.

Article first published here: http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/hugh-gusterson/education-occupation