Young Grassroots Activism on the Rise in Iraq: Voices From Baghdad and Najaf

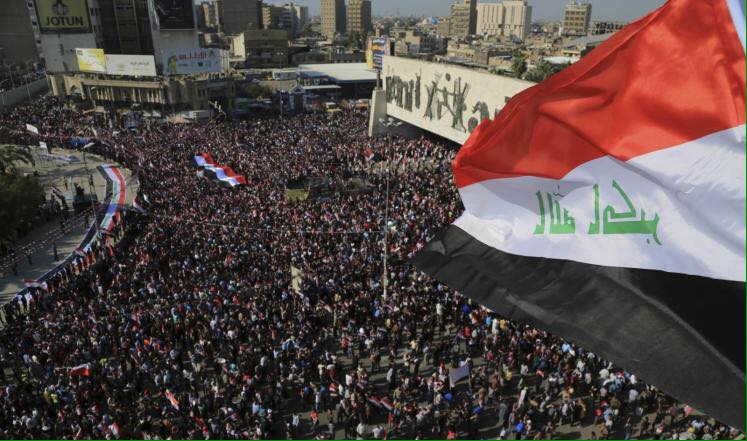

However, al-Sadr’s participation is only a recent chapter in a popular protest that began on 31 July 2015. Launched by ordinary citizens and political activists in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square and across Iraq, this movement has expressed the citizenry’s general exasperation at the corruption and mismanagement of the post-2003 government; corruption and mismanagement epitomised by electricity cuts and a lack of public services. These protests quickly turned into a massive popular movement – supported even by the prominent religious figure Ayatollah Sistani – vilifying Iraq’s post-invasion regime and demanding radical reforms. Every Friday since, demonstrators have gathered in the main public squares of Iraq’s big cities – Najaf, Nasryah, Basra, etc. – and echoed the slogans of the protestors in central Baghdad: “Bismil din bagunah al-haramiyah” (in the name of religion we have been robbed by looters) and “Khubz, hurriyah, dawlah medeniyah” (bread, freedom and a civil state). Demonstrators denounce the sectarian and corrupt nature of the post-invasion political system in Iraq, which has institutionalised ethno-religious quotas and empowered an incompetent and self-interested political elite mainly hailing from exile and conservative Shi’a Islamist groups.

I could sense the disruption caused by the sit-ins to Baghdad’s everyday life, as all the roads leading to the entrance to the Green Zone were closed. It was impossible not to notice the change, as I was obliged to take nonsensical routes to get from one area of Baghdad to another. However, circulating in the capital was not too difficult; the only checkpoints I encountered that were seriously stopping and searching every vehicle were those situated at the entrances to al-Kazmiyah, the neighbourhood where I reside in Baghdad with my maternal family. More generally, there was a sense of excitement and feeling like “something is going to change.” In the streets, in the coffee shops and restaurants, and among the various homes I visited, everyone was following the day-by-day developments of the crisis. Moqtada al-Sadr’s reforms, presented two weeks ago, were screened everywhere and watched by everyone. His statement on the abolition of “communal-based quotas” (al-muhasasa al-siyasiya) – institutionalised by the US-led occupation administration and new Iraqi elite in 2003 – seduced many ordinary citizens, civil society actors and political activists who would generally be very critical or suspicious of the Sadrist leader.

Various readings of the protest movement’s developments

However, some independent civil society groups and leftist political activists, who continued protesting every Friday for no less than eight months, were divided on the participation of (and then the centrality taken by) Sadrists in the protest movement. Falah Alwan and Hussam al-Watany were among the most skeptical of this Sadrist involvement. Two long-standing activists, the elder and younger respectively, I met Alwan and al-Watany in their offices at the Federation of Worker Councils and Unions in Iraq, which is located in central Baghdad. Both activists expressed that the initial “secular” movement has now been “instrumentalised” by the Sadrists. This critique – also expressed in Sawt al-ihtijaj al-jamahiri (The Voice of the Popular Protest), a journal dedicated to the recent mobilisations – is essentially built on a Marxist and secularist reading of political activism. According to Alwan and al-Watany, any reference to religion is a form of alienation and an obstacle to human emancipation. Following this principle, Alwan and al-Watany consider any partnership with Islamists as a potential threat to the movement; a “terrible mistake made by leftists seduced by Islamists’ populism.”

However, most civil society activists I met in Baghdad were far more nuanced. Henaa Edwar – the head of the al-Amal organisation and a prominent figure of Shabakat al-nisa’ al-iraqiyat (The Iraqi Women Network, IWN), the main platform for gathering independent women’s rights activists and organisations in Iraq – was very hopeful regarding the developments of the popular protests. I met her in the al-Amal offices in al-Kerrada, central Baghdad, the day she visited the sit-ins with a delegation of IWN activists. Despite remaining critical of the Sadrists’ populism and conservatism, especially regarding gender matters, Edwar expressed her support for the protesters and a positive view of the Sadrists’ involvement. Henaa Edwar believed that Moqtada al-Sadr’s presence pushed the Sadrists’ wide, grassroot, proletarian base onto the streets in a show of unified nationhood and citizenship, especially at a stage when after weeks of mobilisations, some protesters, tired of being in the streets every Fridays, were starting to go home.

Like Edwar, many other women’s rights activists I met in Baghdad emphasised the importance of linking gender equality advocacy with the struggles for social and class equality. IWN activists insist on the preservation of equal citizenship for Iraqis from all ethnic and religious backgrounds as a cornerstone of the preservation of women’s legal rights. They have, since 2003, insisted on preserving a unified Personal Status Code; a code that has been consistently under threat from the conservative Shi’a political leadership. Thus, despite being aware of the Sadrists’ conservative position on gender issues, many women’s rights activists point to the Sadrists’ nationalist positioning in this particular moment as a positive addition to the struggle for equality.

Saad Salloum, a young author and advocate for ethnic and religious minorities in Iraq, also takes this intersectional position: acknowledging the necessity to overlap the equality of citizens of all religions, ethnicities and sects with gender equality. Salloum is the editor-in-chief of the cultural magazine Masarat, whose offices are located in the Christian quarter of al-Kerrada, just next to a beautiful church and Christian primary school. I met him there, and we had a long discussion about the condition of minorities in Iraq, especially since the Islamic State’s occupation of northern and western parts of the country in June 2014. Salloum insists on the importance of linking the social justice movement to ethno-religious equality issues, and he works at the grassroots level to promote a “culture of diversity” and a concept of “citizenship based on full and unconditional equality.” Salloum is also one of the few researchers and civil society activists in Iraq that has addressed the issue of Afro-Iraqis, as he conducted fieldwork in several communities of Black Iraqis in Basra.

In Tahrir Square

In Tahrir Square, I met radical political activists, poets, authors, academics and women’s rights activists. It was as if, every Friday, the passionate political discussions started in the bookshops of al-Mutannabi Street were transferred – in the form of chanting, banners and slogans – to the square. When I arrived in Tahrir on Friday 1 April, in the afternoon, only a hundred demonstrators were present and mainly consisted of two groups: a group of independent young activists and a group gathered around a banner stating, “The change of ministers outside the communal quota is the first step towards total reform.” The mobilisation that day was not as large as the day Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi announced the formation of a new government. Women, especially young women, were less present than young men in the square; however, of the young women who were present, most were gathered around this banner and followed the chanting of Jassim Alhelfi, a leading member of the Iraqi Communist Party.

Another group, composed mainly of young men, was also chanting and cheering similar slogans – such as “Nihayatkum qariba” (Your end is approaching) – aimed at the post-invasion regime. Dhurgham Ghanem and Jamal Mahmoud, young, independently organised protesters, were among this group and expressed that they would remain mobilised, as they were unsatisfied with these “limited reforms.” They both expressed that this movement has shaped their political awareness and constitutes a first step in organising independent youth groups focusing on issues of imperialism and social justice. According to Ghanem:

“This mobilisation is the continuation of wider activism against imperialism, because of imperialist forces that have institutionalised sectarianism in Iraq through the communal-based quota. It is the direct consequence of the occupation of Iraq and imperialist politics aimed at destroying and ruining Iraq.”

Both Ghanem and Mahmoud spoke about the fact that, as independent grassroots activists, they face difficulties financing their activism and work through independent means. Furthermore, some members of their group, including Mahmoud, have been subjected to violence and arrest from the police and security services.

Other activists I spoke with in Baghdad – such as Dhurgham al-Zaidy, brother of the infamous Muntazar, who threw his shoe at George W. Bush in September 2009 – mentioned the brutality of the state’s “security men.” A prominent independent civil society activist, al-Zaidy several times faced police brutality after participating in the Friday demonstrations in Tahrir Square. While sitting together in the famous Redha ‘Alwan coffee shop, on al-Kerrada’s main street, Dhurgham al-Zaidy spoke about how he and many other young, independent activists have been attacked by unknown men on their way home from Tahrir. According to him, these men are sent by government officials to weaken the popular protest movement and traumatise radical activists. Despite this, al-Zaidy continues his independent grassroots work for social equality and the struggle against poverty. He is not affiliated with a party or financed by any group. It is a courageous choice; a choice that makes him more vulnerable than formally organised groups.

However, protesters also received some support from parliamentarians, such as the famous MP Shirouk al-Abayachi. Before becoming an MP for Al-tahalef al-medeni al-demuqrati (The Civil Democratic Alliance), a secular and liberal political group, al-Abayachi was a prominent women’s rights activist, IWN figure, and environmental and social activist. When I met her in Baghdad two weeks ago, she had just distanced herself from her political group and decided to carry on as an independent MP. We had a very open and lively discussion about her involvement in formal politics, especially as I have known her for several years as a prominent women’s rights activist. Al-Abayachi expressed her support for the protestors from the beginning of the movement and organised discussions, in both public and private gatherings, with the young civil society activists of Tahrir Square.

Moja: radical grassroots activism among Najafi youth

Continuing my discovery of independent grassroots youth activism in Iraq, I travelled to Najaf – about 180 km south of Baghdad – to meet with Yaser Mekki and Muntather Hassan, both prominent members of Moja and students of dentistry. When I arrived at the open door of their coffee-library, it was like entering a completely other world. In contrast to Najaf’s overall conservative and traditionally Shi’a atmosphere, I entered this place off al-Kufa’s main street adorned with books and self-drawn pop art. The coffee-library is run by young men and women, mostly local university students, who have rented these two rooms with their own money. They warmly welcomed me and we began discussing the amazing and original activism Moja started a few years ago.

Their work is very diverse but generally consists of, as Mekki put it, “educating people in critical thinking and freedom of belief”, “motivating them to read as much as possible and as diversely as possible,” and “promoting a culture of social, class, gender, ethnic and religious equality and freedom.” Moja has greatly participated in the national civil society campaign “Ana iraqi ana aqra” (I am Iraqi and I read), which promotes literacy and organises an annual cultural event and distribution of books on Abu Nuwas promenade, on the banks of the Tigris.

However, Moja also works on many other levels, both cultural and political. Despite being completely independent, refusing local or foreign funding, and refusing to join any political parties, Moja activists were at the forefront of the protests against corruption and sectarianism in Najaf. They also regularly distribute giftwrapped books in the streets of Najaf to people passing by, encouraging them to read all kinds of literature.

Moja activists have organised charity fundraisers and humanitarian support for displaced Christian and Sunni families fleeing the IS occupation of their towns in northern and western Iraq. In this context, in order to promote interfaith dialogue and minority rights, Moja activists have also encouraged the inhabitants of Najaf to join their Christian compatriots in the celebration of Christmas. They have erected and decorated a Christmas tree, named “shejerah al-salam” (the tree of peace), on al-Rawan Street, one of the main streets of the holy city of Najaf. Moja activists regularly organise events around philosophical, religious, cultural and political books, inviting authors to present their work and opening a space for debate and free discussion. In only a few years, Moja has managed to gain visibility and popularity among Najafis, as well as the support of some prominent al-Hawza religious figures.

However, Moja also faces discrimination and rejection, including receiving death threats from conservative religious militias. Muntather Hassan spoke about how the owner of the first place Moja rented had received death threats and, hence, asked them to leave just before they officially opened to the public; he did not want the responsibility of renting to a “radical group.” Hassan said: “Having to find a new place and closing this one was pretty painful for us, especially after spending so much time with the other volunteers to paint the rooms and get every detail ready for our opening.” Moreover, Mekki and Hassan are also very much aware that the women of Moja are exposed to even greater pressure and threats, as they are discriminated against both on the basis of gender and due to their refusal to conform to the normative way of life.

This movement of popular protest is similar to the one that emerged in 2011, and specifically targets the general sense of despair and tension that followed the IS capture of Mosul and ensuing occupation in June 2014. Following the call of Ayatollah Sistani in response to IS’s threat to Iraq’s sovereignty, the creation of al-Hashd al-Sha’bi was a turning point. Support for al-Hashd al-Sha’bi is visible in the streets of Baghdad, where one can see banners and pictures everywhere celebrating the glory of al-Hashd al-Sha’bi soldiers and honouring the memory of the nation’s shuhada’ (martyrs). Pictures of these young Iraqi men, soldiers, police, and al-Hashd al-Sha’bi fighters are decorated with Qur’anic verses and visible everywhere in Baghdad and Najaf. Such banners remind citizens of the precariousness of life in Iraq, where death is always inviting itself into everyday life.

However, through banners and slogans, ordinary citizens, politically organised and independent Iraqi protesters have expressed their understanding of the political situation apart from sectarian or communal-based identities. They have peacefully, but no less clearly, expressed the link between corruption and sectarianism with the rise of IS; as one famous banner in Tahrir Square read, “Da’esh and corruption are two sides of the same coin.” In this climate of militarisation, the youth of Tahrir Square and young, independent, grassroots groups like Moja brought new hopeful, creative and inclusive ways of being Iraqi in a country traumatised by decades of authoritarianism, imperialist military occupation, sectarian war and the fragmentation of its territory.