Cultural heritage in times of conflict in Syria and Iraq: a case for prosecution?

By Toon Bijnens, ICSSI

The Hague, December 2015

In a landmark case for cultural crimes, the first person charged with the destruction of cultural heritage appeared recently before the International Criminal Court (ICC), the international tribunal with the jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for crimes against humanity. Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi is an alleged extremist militant accused of destroying ancient monuments in Mali in 2012, among which are ancient mausoleums and mosques in Timbuktu. The destruction of heritage was referred to the ICCI by the government of Mali. The court is now responsible for the investigation and prosecution of the crimes. For the first time, destruction of cultural heritage is prosecuted in an international court. The timing of the case is significant, since over the past year destruction of antiquities in war-torn Syria and Iraq has been in the center of media attention. The ICC case on cultural crimes serves as a strong statement towards those individuals destroying heritage. However, with the conflict still raging on, what are the chances of prosecuting those responsible for destroying cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq? And what are the alternatives when prosecution is still remote?

After the Second World War the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict was adopted with the protection of cultural heritage during international conflicts in mind. This international treaty requires its signatories to prohibit acts of hostility against cultural property, not to use cultural property for military purpose, and to protect it from theft and looting. Both Syria and Iraq are signatories. But what happens on the ground? Most soldiers or rebels have never heard of conventions, and extremist groups such as Daesh do not follow international law.

The chances of prosecution before the ICC of those accused of damaging cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq are still far off. There is little basis to prosecute people in Syria or Iraq, and large amounts of destruction in Syria have been carried out by international militants who flocked to the country to take part in the armed struggle. It is possible to bring them to the court only if the nationality corresponds to a state that signed the ICC treaty. There is a legal basis for prosecution under Article 28 of the Hague Convention, but the Convention is not integrated in the domestic penal codes of both countries. Furthermore, Iraq did not sign the treaty of the ICC, while Syria did sign but never ratified. Both Syria and Iraq have their own national antiquities and heritage law. Although they are stricter than international law, with a strong emphasis on firm sentences, they focus mostly on smuggling and trafficking, not on looting or destruction.

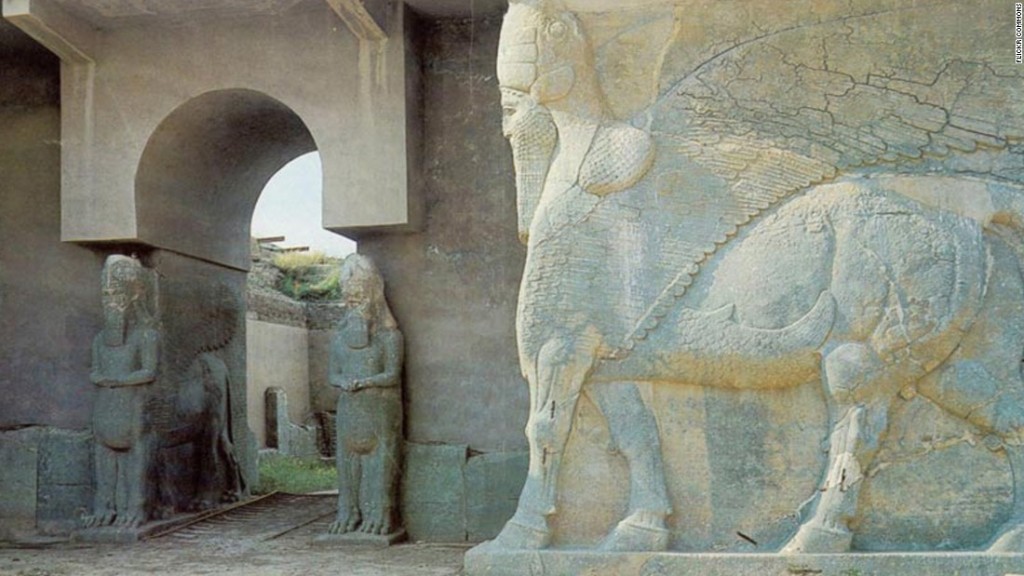

Should an accused be brought before the ICC, it will not be easy to assess the gravity of the crime, or to reflect a degree of priority for damaged heritage in sentences. It is complicated by the fact that damage is inflicted for several reasons, and it is difficult to assess the reasoning or timing behind certain crimes. In the case of Palmyra, Daesh destroyed the Baal temple only several months after its capture. For Daesh, the two main reasons for damaging and looting antiquities are religious iconoclasm and sources of funding. Earlier media stories have covered the trade in antiquities from Iraq. Before accused are to be put on trial, in-depth proof is necessary of the crimes committed. Extensive evidence of the illicit trade was found in May 2015 during a raid in al-Amr, Eastern Syria to capture Abu Sayyaf. The high-level Daesh commander was overseeing the revenue of the group, as the head of the Antiquities Division of the Diwan of Natural Resources. Uncovered during the raid were receipts and plans of looting at archaeological sites in Syria and Iraq, theft from museums, and antiquities which were stocked for ilicit trade. This is important evidence of the archaeological looting committed by the militants of Daesh. Further information on the destruction of heritage that has been unfolded in Syria and Iraq is scarce. One has to rely on Daesh propaganda, or reports from Daesh-controlled areas such as those from “Mosul Eye”. The social media group, based in Daesh-controlled Mosul in Iraq, is currently preparing a report on the crimes against historical and cultural heritage of Mosul, allegedly including registration of events and dates of destruction. Meanwhile in Syria, activists from groups such as Heritage for Peace have been training Syrian citizens to protect monuments and to register damages in archaeological sites. Looking ahead towards the post-conflict period, Iraqi civil society has recommended the establishment of expert teams to inventory sites that have been desecrated or might be in danger of future destruction. This demand is necessary since International organizations such as UNESCO have been criticized for the lack of extensive research on the ground in post-conflict areas where heritage has been damaged, and for claims that “remote” proof (satellite pictures) are sufficient to assess the extent of the damage. Even the director of the Mosul Museum, who fled to the Netherlands, expressed his regrets for the lack of assistance from international heritage organizations. As evident from the cases of Mali and Libya where UNESCO after periods of armed conflict invested in the recovery of cultural heritage through research and capacity building: on the ground-work is essential.

In the absence of prosecution, the international community must look for further ways to minimize the damage and destruction of cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq while the conflict is ongoing. Direct intervention is not desirable and not possible under international law. To prevent the damage to heritage sites, experts have suggested to train the police or the army to protect important heritage sites. Ultimately, states are responsible to protect cultural heritage sites. However, conflict often involves non-state actors, of which rebel groups such as Daesh are an example. The Italian Ministry of Culture earlier this year suggested the creation of a peacekeeping force to protect world’s endangered archeological heritage. UNESCO in October 2015 approved Italy’s proposal to send UN peacekeepers to protect heritage sites around the world from various armed threats. 53 countries alongside the UN Security Council members supported the suggestion. The idea of an antiquities police force has been criticized for its legal limitations. Furthermore, it is a controversial proposal as in many countries (such as Italy) heritage is suffering not from armed conflict, but from lack of maintenance.

Others have suggested the creation of a non-strike list, which would mean a list of heritage areas to be exempted from airstrikes by all means. Though one has to think creatively in order to safeguard cultural heritage, is such an option feasible? In the absence of a solution on the ground, the struggle against illicit trade in antiquities is ongoing, and it takes place mostly outside of Syria and Iraq. According to Iraqi lawmakers Western countries, where most of the trade takes place, have a particular responsibility to bear. A red list of artifacts at risk in Syria and Iraq has been published by the International Council of Museums, a network of the global museum community which has a consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. The red list illustrates items that are likely to be illegally traded in order to identify objects that are at risk. However, the list is far from exhaustive. Meanwhile, new ideas and plans are proposed to monitor stolen antiquities and to reconstruct damaged heritage. Ultimately, the key to heritage protection in Syria and Iraq is depoliticization and international cooperation; heritage knows no borders.