Study Shows that Despite Trauma, Journalists in Iraq Dedicated to Profession

Source: University of Kansas

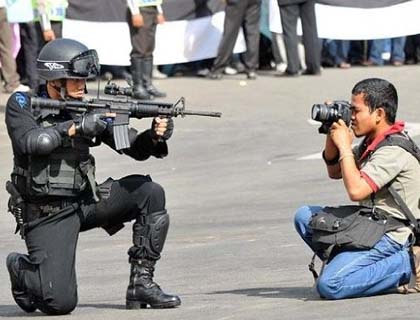

During the war in Iraq, journalists from around the world flocked to the country, covering violent events from the battlefield to the halls of political power. But they eventually got to go home. Thousands of journalists still work in Iraq, and though the war is officially over, they still cover violent events regularly and are often targets of violence themselves. Two University of Kansas researchers have conducted a study to see how that regular exposure to violence affects journalists in Iraq and found that fear and resilience are part of their daily lives.

Barbara Barnett, associate professor of journalism, had conducted research into post-traumatic stress disorder in journalists and how it is presented in the media. Goran Ghafour, a doctoral student at KU, is a native of Iraq and had worked as a journalist there for 10 years as a reporter in the field, editor-in-chief of the Kurdistan News Agency and as a novelist, having published three books on the Middle East. They decided to explore how exposure to violence affected their work and lives and whether they had been victims of violence personally.

“Journalists don’t have a lot of help when it comes to post-traumatic stress. They often don’t know they even have it,” Barnett said. “We were thinking about research projects we could do on the topic and came to this topic.”

Ghafour conducted email interviews with nine journalists in Iraq, examining how they view violence, what strategies they use to work safely in dangerous environments and if working in violent environments affect journalists’ emotional well-being. The journalists were men and women from around the country who held a variety of jobs. Some were full-time, others were freelancers, and they worked for a variety of media outlets, though none worked for state media. A 10th interview subject went missing during the interview period and was later reported dead by The New York Times.

“It’s a very different landscape in Iraq,” Ghafour said. “You have government media, media controlled by political parties, opposition media and private media, such as a businessman who owns his own outlet, including TV.”

Two main themes were immediately evident from the interviews: Journalists who covered violent events experienced fear regularly, but they were resilient.

“I’ve started something, and it’s going well with me, and I cannot leave it because of fear. As long as people live, there is fear, so it’s better to work with fear, not sit down and do nothing,” one survey respondent said.

Nearly all of the respondents had been victims of violence or received threats against themselves or families at some point in their careers. All said they knew colleagues who had been threatened with violence, while three reported knowing a journalist who had been killed. Since 1992, 166 journalists have been killed in Iraq.

Exposure to violence, both in covering it in their professions, and experiencing it personally, has taken a toll. Nearly all reported classic symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as insomnia, anxiety and re-experiencing the traumatic event.

But despite the risks, respondents repeatedly said they did not intend to leave because the job of informing the populace was worthwhile and helped make a better society.

“Not only are they in danger, they often face family pressure to leave. This is a very dangerous job. But Iraqi journalists are very brave and resilient,” Ghafour said.

All of the respondents did say that they have the option to turn down assignments if they feel it is not safe to perform and had received some sort of training from international media organizations such as Reporters Without Borders on how to stay safe while working in dangerous situations. Conversely, they also reported often being without protective gear such as helmets, body armor and gas masks. The authors recommend international media and news advocates help journalists in Iraq by providing more training and protective equipment.

“The journalists didn’t necessarily get training on how to take care of themselves the next day,” Barnett said of experiencing trauma. “Journalists often don’t feel entitled to suffer. Even when they are direct victims they often say they were ‘just a witness.’ Iraqi journalists are living like this every day. Journalists who cover combat or other violent situations, then leave those situations, can experience some of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress. In this research project, we wanted to look specifically at journalists who encounter violence every day and who witness violence for years and years with no respite.”