THE OTHER BAGHDAD

By Francesca Borri, Freelance Journalist (June 2015).

We usually simplify Iraq, and its 35 million population, by splitting it into a Shia south, a Sunni centre, and a Kurdish north. Each city, yet, each area of Iraq is rather a blend of different ethnic groups and confessional communities – or of Iraqis who see their common religion, their common descent, in different ways. On the whole, it’s true, Shia comprise the majority of the population, about 60 percent: but rather than a majority and a minority, in Iraq there are just patchworks of minorities. And where a group prevails, you soon realize that it is because of wars and violence. Of forced transfers, of prevented returns – homogeneity, in other words, is far from being natural: it is man-made. In Iraq, and not only in Iraq, the natural state is coexistence.

That’s why there is one decision the United States are especially blamed for: once overthrown Saddam Hussein, they set up a political system where every appointment, every position, and also every contract, now, is linked to sectarian affiliations. Like in Lebanon. Or Bosnia. Today in Iraq the head of state must be a Kurd, the prime minister a Shiite, the speaker of Parliament a Sunni. Regardless of anything else. Of their skills, and most of all, of the election results. Of the popular will. A system based on the wrong assumption of the incompatibility of Sunnis and Shias, and that ended up fulfilling its own prophecy, many Iraqis complain – it did not ratify pre-existing divides, they say: it rather promoted fragmentation.

We focus on ethnicity, on religion, on collective identities, and yet, there is a group that goes to-tally unnoticed, in Iraq: the Iraqis you come across every day. Iraqis from all backgrounds. All ages, all classes, all areas of the country. While Sunnis and Shia clash in the streets, they just wait locked into their homes for the day all this will be eventually over.

Ahmad, 31

“In the name of respect for culture, for traditions, diversity, and countless other nonsense claims, we lost our reason, and fabricated explanations and justifications for things we shouldn’t explain and justify. Because the true problem, here, is religion. But do you think it’s normal that we are all here asking each other whether we are Sunni or Shia? And who the Yazidis, who the Shabaks are, whether they worship the Virgin Mary, a tree, or a rock? Baghdad gets periodically stuck in these surreal pilgrimages, people who slam their heads on the doorjambs of mosques, who kiss floors, books, paintings, chain themselves up, whip themselves, every day there is a martyr, there is a mi-racle to celebrate, and in the weirdest way – but did you see them, last week? They gathered here from all over Iraq by crawling on the ground, I mean, seriously, crawling: like giant frogs. Miles and miles. Crawling. And they curse, they stab each other, they blow up: for something that eve-rywhere else would be no more than a tourist attraction. If I must end up roasted by a car bomb, at least be it for a noble cause. The melting of glaciers, famine in Africa. A treatment for cancer. But not for a light pole proclaimed saint. And in Europe, you defend all this in the name of respect for the local culture, the local society. But who decided that Islam is Iraq, that there’s nothing else, here? Only Sunnis and Shia, and scattered nuts? An identity is not a black and white label. It’s much more complex and plural than that. I am local, too.”

Zee, 23

“I was in the Baghdad belt, I was filming other things. But I walked around, in these dusty alleys, and I don’t know, amid these collapsed buildings, these empty homes: there was something stran-ge. Then I realized. There were no men. Only women. All men had been killed. And there was this old woman who had lost everybody, her husband, her sons: her grandsons, really, everybody: and she had been crying so much, desperately, and for so long, for years, that she was blind. Can you imagine what it’s like, for a child, to grow up in such a place? Such a hell? I am a documentary maker – and that’s why I work on social issues. On that marginality, that misery, that inequality that are both the cause and the effect of violence, and yet, that media usually neglect to focus only on the frontline. On fighters. Without ever wondering where the fighters come from. Their back-grounds, their reasons. And also because I believe that storytelling can be a change maker. It’s not only about exposing events. About being an eye-witness, and keeping track. Keeping memory. It’s not only about the future. Watching one of my TV documentaries on beggars, a father recognized his son, a boy kidnapped four years earlier, and the police could eventually free him. Now I am working on the traumas of war. An issue nobody talks of, because in Iraq asking for specialist ad-vice, for specialist support, is seen as a humiliation. But if you are in your thirties, here, if you are in your twenties, war is the only thing you have experience of. In Iraq violence is not a matter for negotiators anymore, it’s a matter for psychologists.”

Ammar, 21

“I come from a family of hardliners. I come from one of the poorest, and most dangerous, slums of Baghdad. A Shia neighborhood where everybody belongs to a militia. And that’s what I wanted to be as a child, too: a fighter. Because as a child, you are told of fighters as kindhearted, brave guys, ready to die to defend you. To bring justice. A slum is a slum: you are completely cut off from the outside world. The pressure to conform is… is… it’s not even pressure: because there’s one model only: and it is out of the question, because nobody knows that that’s not the only way things are. One day, yet, I happened to enter a theatre: and there was a performance on the neighborhood I lived in. Viewed critically, of course. Or more exactly: from a standpoint I had never thought of. Our fighters were not heroes, but rather thugs. Moved not by ideals, but by money and power. And that’s where it all began, for me. The curiosity for what was going on beyond the borders of my little world. I realized that I am a person, not a Shiite. I’m not my family, I’m not my neighbo-rhood – where nobody approves my choice, of course, I’m a student, I’m not a fighter: I am a trai-tor. But I wouldn’t end up on some frontline, defending my country. I would just end up bullying in the street with an AK47 and a balaclava, genuinely convinced to be strong, like all the friends I grew up with. Who never saw anything else, in their life. They believe they are the strong ones, and instead, they are the ones under attack, the ones to defend, vulnerables – because they don’t exist. They are simply what their environment decided they had to be.”

Ahmed, 24

“There aren’t good or bad books, in the end, only books you feel close to, you are captivated by, or books you aren’t – but one of the poets I love the most is Rilke. Rilke when he writes: Life is short, but the day is long. Because Baghdad is a city that boosts your energy. In Baghdad nothing is ever enough. You are never done. Because it’s a city of diversity. A city that keeps a hint of each of its inhabitants, layer upon layer. Generation after generation. Everything, here, refers to another sto-ry. Holds another world. Everything reminds of another time. Baghdad is a hotbed of imagination. And also, when you live here, you are used to live… to live an in-depth life. Absorbed by complex issues, endlessly faced by moral and intellectual challenges. The identity. The other, the differen-ce, the exchange. The mutual recognition. Justice. Dignity, freedom. Compromise. Or struggle, perhaps, resistance – for you, these are topics for a PhD program: here it’s a tea with friends. But I love Rilke for a second reason, too: because it’s a name that nobody expects from an Iraqi. Accor-ding to you, and to many Arabs as well, Rilke doesn’t belong to my culture. I am black, yet, my fo-refathers were from Kenya, and I like Rilke, and I like Roth and Franzen and dance music simply because that’s what I like. We are not only our traditions. Everyone looks at the past, here. But in the end, we are what we want to be. We are but the product of ourselves.”

Hisham, 32

“I don’t have any feeling for Baghdad. And truthfully, it’s time to get rid of this rhetoric about pla-ces. Your roots. Your homeland. Baghdad for me has no meaning. No value whatsoever. If I think of Baghdad, I only think of my friends. Of my life. I don’t care anything else. Everybody asks you to sacrifice yourself for the sake of your country, of your people: but did my country ever sacrifice itself for me? What did I get from Iraq? My brother died of a common disease. A treatable disease. And it wasn’t because of the sanctions, it wasn’t because of lack of medicine. It wasn’t because of war, of poverty: because of the United States: of Sunnis and Shia: no, my brother was simply killed by negligence. By ignorance and malpractice. We asked for an autopsy, at least, we asked doctors to examine his case, and learn from their mistakes: they never answered. A stupid death: and also a useless death. In this country nothing works, and everyone blames Bush, blames Bremer, blames religion. But no one strives to improve things. No one tries to be a doctor with professionalism, in-stead of wasting his time arguing over Iran and Saudi Arabia. Here you are asked to fight, to be a loyal citizen, not only to pay taxes and obey the law, you are asked to risk your life, but for what? It’s time to focus on people, rather than places. Time to forget maps, forget geography, and instead of asking ourselves what this city means to us, what connects us to this country, ask ourselves what we mean for us: what connects us each other. It’s time to reverse priorities. As James Joyce said: Let my country die for me.”

Murtadha, 23

“My dream is to become a photographer. I have two dreams, actually: the second is to drink red wine. Because my best friend is Italian, he’s from Pavia. Nicola. He studies Geology. We met three years ago in Istanbul, and since then, we have been joined at the hip. But only on Facebook, Wha-tsapp and Skype, because for a young Iraqi there’s no way to get a visa to Europe. Nicola’s parents are doing their best to help me with papers, with the embassy, because the application procedure is a labyrinth, you need three invitation letters, a health insurance, a bank deposit of several thou-sands dollars: and a final interview, too, like a bachelor’s examination – but of course, everybody think that a 23-year-old Arab is coming to Italy to stay. That he won’t leave. And so I have never been called for the interview. Also, your application is declined without any explanation: and you can’t even understand if it makes any sense to try again. But I don’t want to move to Italy. We are not all packed-up and ready to leave. Europe, for me, is a different, odd world the same way for you the Middle East is. I wouldn’t adapt and feel at home just because I can find a kebab down on the corner. I want to live here. I simply want to travel, like you, I want to go and come back – and in Italy, see the settings of the movies of my favourite film-maker: Giuseppe Tornatore. I want to see Sicily. I don’t understand why you are so self-centered. At the beginning also my family, not only Nicola’s, was wary. His parents were afraid I could be an Islamist, a terrorist. But my parents, too: they were afraid of this stranger who could be a drug smuggler, an arms trafficker. Because an Italian, no?, is dangerous. The Mafia is everywhere.”

Mahmoud, 19

“The foreign country I am most curious about, actually, is the Green Zone. I can’t enter, it’s the only area of Baghdad I have never been into: I have no idea how it looks like. And it’s the seat of power, in the end, it makes no sense: you wage a war, and you leave behind one million dead, to topple a regime, that is, power exerted with no control, no accountability, and then you replace it with the same sort of power: off limits to citizens. I mean: truthfully, I’m not curious at all. I’m not sorry because I can’t hang out with the Green Zone guys. It’s just a bunch of idiots. I mean, becau-se it’s crazy, c’mon, I have no clue who they are and they have no clue who I am: only, they want to change me – to modernize me. But the only thing they know of Iraq, is the road to the airport. And also this story of living entrenched there. This is Iraq. This is our place, there’s no point in building barriers: we will always find a way to hit them. Security doesn’t come from walls, it’s the opposite, it comes from mutual acquaintance. From trust. Even though, truthfully, this is only the instinct. I mean: to believe them a bunch of idiots. Because at the same time, it’s like having a con-stant doubt: are they wrong, or am I? It’s like living in the shadow. With this ghost that overlooks you, and reminds you every single moment that you are nothing, you, your culture, your society, we are but archaic remnants of a dark age. Everywhere else, everybody is smarter than us. And how can I rebuild Iraq, if I am not confident in myself? Perhaps that’s, here, the most dangerous form of insecurity.”

Find Francesca Borri on Twitter @francescaborri and Facebook

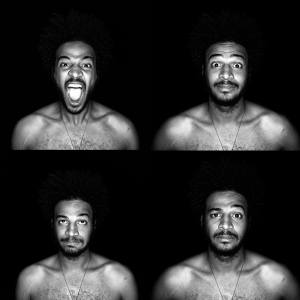

[all photos by Ali Arkady ©VIIPhoto]

[These portraits belong to “Happy Baghdad”, a long-term project by photographer Ali Arkady. You might actually think that these young Iraqis are an exception: seven mavericks out of 35 million of Sunnis and Shia. Of fighters and refugees. They are not. So far, Ali Arkady has collected about 50 portraits. Fifty stories, fifty challenges to the mainstream image of his country. And he is going on]