Will Turkish Defense Minister’s Iraq Visit Yield Concrete Results?

Although Turkey’s defense minister seems to be satisfied with the outcome of his recent visit to Baghdad and Erbil, there are several impediments to Turkey’s security demands.

Turkish Defense Minister Hulusi Akar’s recent visit to Iraq has seen plenty of verbal agreements on an array of issues Ankara shares with the central Iraqi government and Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Yet whether these agreements would translate into concrete steps remains to be seen.

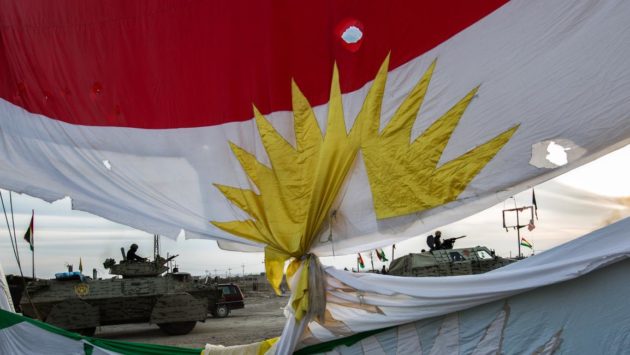

Following Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s visit to Turkey Dec. 17, 2020, Akar paid a high-profile visit to Baghdad and Iraqi Kurdistan on Jan 18-20. He was accompanied by a large Turkish delegation including Chief of Staff of the Turkish armed forces Yasar Guler. In Baghdad, the delegation headed by Akar met with the Iraqi minister of defense and minister of interior along with President Barham Salih and Kadhimi. In Erbil, Akar held separate meetings with KRG President Nechirvan Barzani, Prime Minister Masrour Barzani and former President Massoud Barzani, who is also leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the dominant political force in Iraqi Kurdistan. The delegation also paid a visit to the office of the Iraqi Turkmen Front in Erbil.

Eight meetings and the high-profile welcome indicate the importance the Iraqi side attached to the visit considering the cold shoulder the Iraqi authorities gave to the Turkish defense minister only months ago. Akar’s previous planned visit to Iraq in August last year was canceled after a Turkish drone strike killed two Iraqi border guards in the Sidekhan area in the same month, as part of ongoing Turkish military operations against the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) members based in northern Iraq. Turkey and much of the Western powers including the United States consider the PKK a terrorist organization.

The first sign of breaking the ice came with Kadhimi’s Ankara visit last month that took no less than four invitations by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Akar’s follow-up visit has further boosted the expectations that the two countries were ready to settle their differences.

During Kadhimi’s visit, the sides discussed a large array of bilateral issues, including strengthening the security cooperation against the PKK, removing PKK militants from Sinjar and Makhmour, opening of a second border crossing between the two countries, reconstructing a main highway linking Mosul to this crossing in an attempt to set up a buffer zone between the PKK-based regions of Iraq and Syria’s region under the control of the Kurdish groups, reopening of an oil pipeline from Kirkuk to Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, setting up joint modernization projects to solve the chronic water-sharing problem between the two neighbors and developing reconstruction projects that were planned to be financed through a $5 billion Turkish pledge for Iraq’s reconstruction.

Coming only days before US President Joe Biden’s inauguration, Akar’s visit mainly focused on security issues. The visit was aimed at building on the momentum generated by Kadhimi’s visit to curb Iraqi objections against the Turkish military operations against the PKK, and forcing Baghdad and Erbil to maximize their cooperation on this front before the new US administration steps into the calculation. Debilitated by the Baghdad, Tehran and Ankara triangle, the Iraqi Kurds hope to find room to breathe under the new US administration policies. Likewise, the Syrian Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces also hope the US approach would rein in the Turkish aggression in Syria.

Will the high-profile meetings that Akar held in Baghdad and Erbil mean concrete steps in favor of Turkey?

According to Akar, both sides are almost on the same page in most of the bilateral issues, particularly on the security front. “We have agreed on many issues,” Akar said during a press conference at the Turkish Consulate in Erbil. “The mutual talks between the two delegations will continue. I believe that these will yield positive outcomes on the ground soon,” he noted. He stressed that the Iraqi Kurdish authorities’ willingness to cooperate with Turkey in the fight against the PKK “was very meaningful” for Turkey.

In addition, he said that both sides discussed the implementation of a security deal between Erbil and Baghdad that Turkey hopes would lead to the removal of the PKK militants from the Sinjar region. According to Akar, the PKK militants “will soon be removed from the region through measures to be taken in the near future.”

“We have repeatedly expressed that our fight [against the PKK] will continue until the last terrorist is eliminated,” Akar added, thereby summarizing Turkey’s expectations from the visit.

Yet, despite Turkey’s determination to fight against the PKK from the Qandil Mountains on the Iraqi-Iranian border to the western Syrian border, the verbal consensus between the Turkish and Iraqi authorities have so far failed to translate into concrete achievements on the ground and are unlikely to produce any results in the near future. This means that Turkey’s military approach to seek a solution to its deep-rooted and decadeslong Kurdish problem through cross border operations in neighboring countries will continue to mar the joint projects between the two countries.

The PKK presence in the Sinjar region was the focal point of Akar’s visit, according to sources in Baghdad and Erbil who have knowledge about the visit. Accordingly, Turkey gauged Baghdad’s reaction to set up new military checkpoints to the west of Mosul in order to force PKK members to leave Sinjar. Yet the sprawling number of Turkish checkpoints, particularly the Turkish military presence at the Bashiqa military base near Mosul, is already a point of contention between Ankara and Baghdad, with the Iraqi side having protested twice against Turkey’s refusal to withdraw its forces from Bashiqa. A prospect for a permission to new checkpoints seems highly unlikely under such circumstances.

The Sinjar deal between Baghdad and Erbil that calls for the deployment of central government forces in the region has also failed to produce the desired results Turkey has hoped for. Ankara considers the local Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS) as a PKK affiliate and asks for its dissolution, while Baghdad wants to integrate the YBS into the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) in order to avoid a possible military confrontation.

Moreover, pro-Iranian PMU factions that hold sway in areas where Turkey wants to set up new military checkpoints stand as another obstacle before the Turkish demand. There are also political opposition blocs that are against Turkey’s further involvement in Mosul and other Iraqi regions. The Turkish proposal for a second border crossing in Ninevah has been shelved partly due to the objections by these blocs wary of increasing Turkish influence in the predominantly Sunni region. Turkey’s proposal aims at bypassing Iraqi Kurdistan to set up direct trade links between Turkey and the central government also has potential to disrupt Erbil-Baghdad ties. While Turkey helps the Iraqi government to counterbalance the Iranian influence, Kadhimi does not want to risk the support of major political forces in Iraq ahead of the general election in October.

Baghdad’s reluctance, meanwhile, may lead Turkey to turn to the KDP-controlled regions for the new checkpoints. Yet proximity of these areas to the Semalka-Fishkhabour crossing — the only link that connects the Kurdish-controlled northeast of Syria to foreign trade routes through Iraqi Kurdistan — stands as a major impediment before this plan. During Turkey’s 2012 military operation against the Kurdish groups in northeastern Syria, the United States prevented Turkey from having bases near the Semalka-Fishkhabour crossing, wary that Turkish interventions could cut off the only lifeline the Syrian Kurds have. Erbil probably would not favor the idea out of similar concerns.

As for Turkey’s demands on the Makhmour camp, an area home to a refugee camp that hosts more than 12,000 Kurds who fled Turkey in the 1990s, the Iraqi Kurdish sources believe that Baghdad may opt to disperse the camp by granting Iraqi citizenship to its residents.

Sources believe that although the Barzani family is eager to boost cooperation with Ankara, it does not want to be dragged into the conflict between Turkey and the PKK.

The fatal clashes between PKK militants and peshmerga forces Dec. 13 in Gare has served as a bitter warning for the KDP against a possible intra-Kurdish fight. The region was alarmed by the specter of another fratricide similar to the intra-Kurdish bloodshed in the 1990s. The incident prompted calls for restraint by intellectuals and politicians. Direct confrontations between the PKK and peshmerga forces under the KDP also threatens the ties between the KDP and its coalition partner Sulaymaniyah-based Patriotic Union of Kurdistan — the KDP’s main political rival that has been on better terms with the PKK. A possible escalation may lead to the division of the region between Sulaymaniyah and Erbil.

Moreover, both Baghdad and Erbil would probably want to see the extent of the change that the Biden administration will bring on the ground before bowing down to any Turkish demand.