Building Solidarity with Migrants, Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in the Time of the Coronavirus

With one of the world’s largest populations of migrants, refugees, and internally displaced persons (IDPs), many of whom live in overcrowded camps without adequate healthcare, sanitation, food or clean water, the Middle East could be the site of a COVID-19 outbreak that exceeds the devastation in Europe and the U.S. While we are all at risk from infection by the Coronavirus, it is the poor, the homeless, and those driven from their countries and communities by violence and war who are most vulnerable. The ICSSI’s 4th webinar on solidarity in the time of the Coronavirus gave participants an opportunity to hear from those on the frontlines of providing support and hope for immigrants, refugees and IDPs in Iraq, Syria, Greece, Italy and the U.S. They inspired us with stories of how people in different nations are developing greater understanding of migrants’ struggles and are stepping up to help. People now also appreciate the important and vital skills immigrants bring to their new homes. In the U.S., despite President Trump’s virulent attacks on migrants, the government is issuing visas to those with medical skills. Now people are saying, “Immigrants should be welcome. They may be the ones who save your life!”

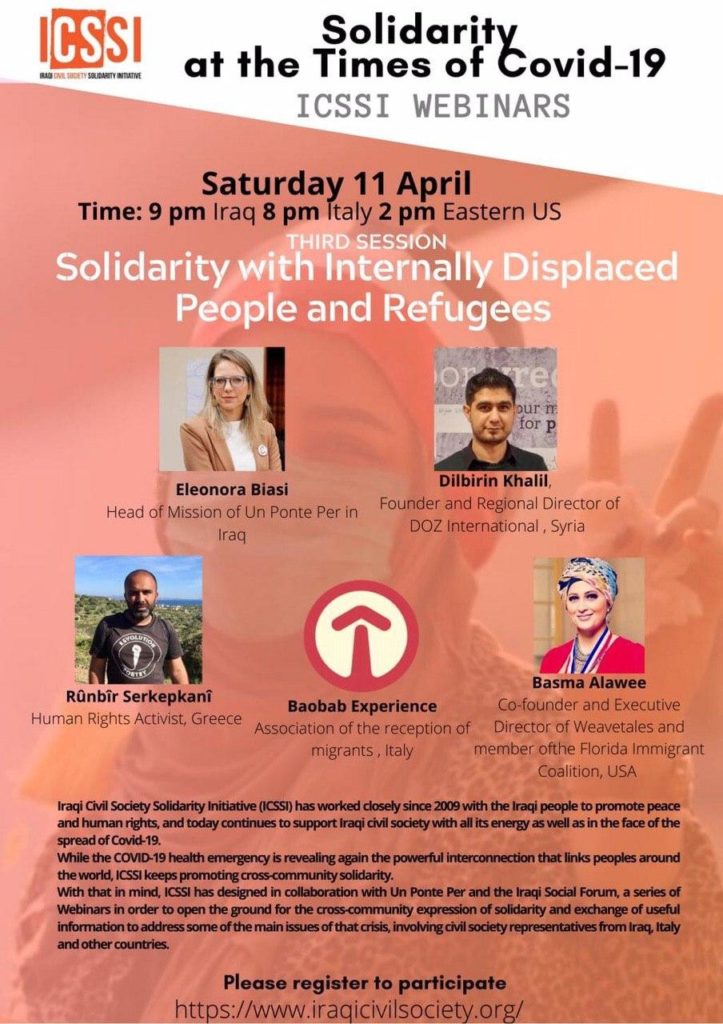

Our five experts were:

- Eleonora Biasi is the Head of Mission in Iraq for Un Ponte Per (UPP) an Italian organization.

- Dilbirin Khalil is the Founder and Regional Director of DOZ International in Syria.

- Rûnbîr Serkepkanî is a human rights defender, environmentalist and writer; he has worked with refugees in Greece for over four years and currently serves as a program support coordinator with Aegean Migrant Solidarity.

- Andrea Costa is an activist in Italy, working to support refugees and migrants through the Baobab Experience.

- Basma Alawee is the Co-Founder & Executive Director of WeaveTales, which collects and shares refugees’ stories from around the world; she is also a member of the Florida Immigrant Coalition in the U.S.

They began by sharing information about the situation of migrants, refugees and IDPs in their countries.

Iraq

At what is a very complicated moment (following months of protest about government services and electoral reform) Eleonora Biasi said the large populations of IDPs and refugees in Iraq face exceptional risks from COVID-19. Today there are approximately 1 million IDPs, 200,000 of whom live in camps: there are also 250,000 refugees in camps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). COVID-19 cases are growing daily. More than 1000 infections are officially confirmed; Ms. Biasi fears the number is higher. The Iraqi healthcare system functions poorly and is not doing extension testing for the virus. Conditions in the camps are particularly difficult as residents are over crowded; people lack access to basic hygiene; and healthcare is limited to nonexistent. In the IDP camps people live in tents and share bathing and toilet facilities with other residents; the refugee camps mostly have facilities for each family. In response to the epidemic authorities severely limited access to the camps by humanitarian aid workers who normally delivered food and medical care. At the same time, residents can no longer leave the camps to work in order to support their families. While these precautions are important to limit the spread of COVID-19, many people are suffering from fear and at risk of starvation. Domestic violence and mental health problems are increasing. The WHO declared the living conditions in the Iraqi camps, combined with the fragile Iraqi healthcare system and the threat of food shortages a “recipe for a developing disaster.”

Syria

Dilbirin Khalil reported that conditions for refugees and IDPs in Syria are also dire. While the official numbers of COVID-19 cases are quite low, these reports likely underestimate the reality. There is currently no testing being done for the virus, so we do not know if it is spreading in the camps. The situation is the worst in the north of Syria where the government is not in control; people there lack even food, let alone sanitary or medical supplies. War and conflict made access to the camps difficult; now fear of spreading COVID-19 is further restricting the movement of humanitarian aid workers. Organizations are increasingly unable to deliver food, supplies or medical care.

Greece

Rûnbîr Serkepkanî described the situation of refugees in Greece, providing vivid details of the camp on Lesbos where he works. In March, Turkey opened its borders and Greece experienced a flood of refugees entering by both land and sea. Greek Islanders were outraged; activists from both the left and the right denounced Turkey—over health concerns and out of anti-immigrant sentiments. Greece announced it was suspending all asylum applications. Turkey then reclosed its borders and, following Greece’s COVID-19 “stay at home” order, the flow of refugees drastically slowed. But on the island of Lesbos, the refugee camp built to house 2,500 is now home to 25,000 individuals. There are no bathing facilities and no clean water; the toilets are temporary; proper hygiene is impossible. There may be one doctor for every 1000 to 2000 camp residents, but the doctors have no medicines. There is also tremendous violence in the camp; recently a young man was killed. Mr. Serkepkanî called the camp a “concentration camp” and a COVID-19 “hotspot” in the making. In 2016, Greece and Turkey had agreed that some refugees in Greece would be deported back to Turkey, but now those individuals are essentially imprisoned in Greek camps where they are victims of violence and repression, including attacks by the police. Recently, camp residents staged a hunger strike to protest police brutality.

Italy

Andrea Costa began by saying that the number of migrants in Italy is unknown, as thousands are homeless and living in streets. Many are attempting to transit through Italy, hoping to ultimately settle in northern Europe. The previous Italian government passed a law denying social services to migrants, and as a result they were thrown out of temporary, transient shelters. Mr. Costa’s organization provides support for homeless migrants in Rome, supplying food, blankets, and medical care. Recently, they began educating people about the spread of COVID-19, and distributing gloves and masks. During the current lockdown in Italy, government offices that process applications for asylum are closed, but Mr. Costa predicts that when the lockdown ends there will be thousands of new applications. On an optimistic note, Mr. Costa observed that Italy’s devastating COVID-19 crisis is having a positive impact on Italians’ understanding of migrants. People are realizing that disease, not migrants, is the threat, and more people are asking how they can help. It seems that Italians with the Coronavirus are more dangerous for migrants than migrants are for Italians. In order to continue to build solidarity with migrants, Mr. Costa tells stories of their struggles. While Italian ports are currently closed, there are vast numbers of migrants who want to enter Italy when they reopen, and he hopes they will receive a more compassionate welcome.

U.S.A.

Basma Alawee began by offering thanks for all that she was learning from the other speakers. In the U.S, she explained, there are two government offices that interact with refugees and migrants: the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). There are currently 521,000 migrants who have applied with USCIS to enter the U.S., but because the immigration system was shutdown in response to COVID-19 some deadlines for deciding on these applications have been extended. However, ICE continues to arrest undocumented migrants, although not in hospitals or healthcare centers, so that they do not fear seeking medical care. Testing for the virus is finally free to all, but undocumented migrants do fear getting a test. Asylum seekers at the Mexican border, including unaccompanied children, are being turned away; those seeking asylum through other ports of entry are sent back to their countries of origin. The federal government has made financial aid, including unemployment payments and cash assistance, available to U.S. citizens, but that does not help immigrants. Therefore, Ms. Alawee explained, her organization supports five policy changes:

- Migrants, whether documented or undocumented, should be eligible for unemployment payments and cash assistance.

- Migrants and asylum seekers should be released from detention camps.

- Detention and deportation of asylum seekers should immediately cease.

- Services for immigrants should receive federal funding of $600 million.

- It should be easier for migrants to obtain permanent U.S. residency.

Common Issues:

Continuing Migration, Delivering Services, and Utilizing New Technologies

In Iraq, severe restrictions on movement and access to the camps have inspired innovative solutions to provide support for refugees and IDPs, Ms. Biasi said; for example they are using online platforms to offer psychological counseling and support for women facing domestic violence, and to provide education about COVID-19 and prevention measures. Fortunately they can still deliver medicines. In Syria, Mr. Khalil described a more severe breakdown in support services. The Internet there is very poor so it does not help. After March 15, all education in Syria was halted, and although some classes are now taught via What’s App, there is no education in the camps. In northern Syria, new camps for IDPs were being constructed but they are not finished. While the flow is diminished, refugees continue to come to Greece. Since the COVID-19 epidemic, new arrivals were all put on a military boat that was like a prison in the harbor. The government was going to deport them to Turkey but later moved them to a camp on the mainland where they were quarantined. In Iraq, another concern is the government’s plan to close all IDP camps. It is very difficult to track people once they leave the camps to provide support. Forced evictions and camp closures started last year; people were sent to their places of origin or to other camps. Exactly when more closures will occur is unclear.

Building Solidarity

Mr. Costa reiterated that popular understanding of immigrants’ situation in Italy is improving. To make this change permanent, he shares stories about the contributions of immigrants. Previously Italians were afraid that immigrants were stealing their jobs, now they realize immigrants work in the fields and pick their food. They appreciate how “we are all on the same boat.” Freedom of movement is a fundamental human right; at this moment we are all experiencing how COVID-19 has limited our movement, so we can empathize with migrants who must move to save their lives and provide for their families. The Pope has been preaching that it is time to stand with those who lack homes and food; now there is a campaign to insure migrants’ in Italy can access healthcare (which was successful in Portugal). After many years of racism and rejection of migrants, maybe we can be optimistic, Mr. Costa concluded. With all the sickness and death COVID-19 has brought, this could be one good thing.

Mr. Serkepkanî reminded webinar participants that while COVID-19 was spread throughout the world by rich people able to travel freely, who encountered no walls or closed borders, migrants and refugees fleeing war and violence do not have the same freedom. These inequalities should be a call to action for us all.

Ms. Alawee emphasized that all governments must understand the difficulties migrants face—this is an opportunity to end discrimination. She described how President Trump tried to use the epidemic to promote building “The Wall.” Immigrants responded with a “Virtual Rally” to say that the money would be better spent on healthcare resources, while the construction workers could be building facilities to care for people. We must all do what we can to insure migrants’ access to health care, Ms. Alawee concluded. Everyone should support immigrant campaigns and organizations, stay informed, share awareness through social media, volunteer for an immigrant organization—staff their hotlines, translate materials.