Building Solidarity Among Teachers and Students in the Time of COVID-19

No nation will enjoy security, democracy, and human rights if it fails in educating its next generation to assume informed and just leadership. While the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed unprecedented demands on educational systems throughout the world, it is also producing remarkable discussions among teachers and students, at all educational levels, about how to continue education during the COVID-19 crisis. But more importantly, these discussions are inspiring thought and solidarity about shaping more effective systems of education that can create a more just, compassionate and equitable future. Participants in ICSSI’s third webinar on responding to the Coronavirus pandemic were inspired by reflections from speakers from three countries—Iraq, Italy and Sweden. In the future, beyond this moment of pandemic, the ICSSI plans to provide a platform for continued discussion about education. We believe these discussions will help build a world in which citizens are better prepared to participate in advancing their societies and addressing the global challenges we jointly face.

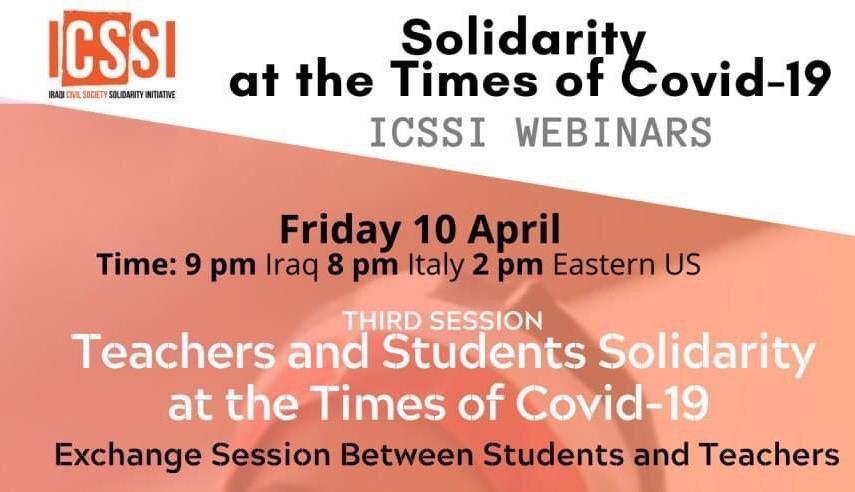

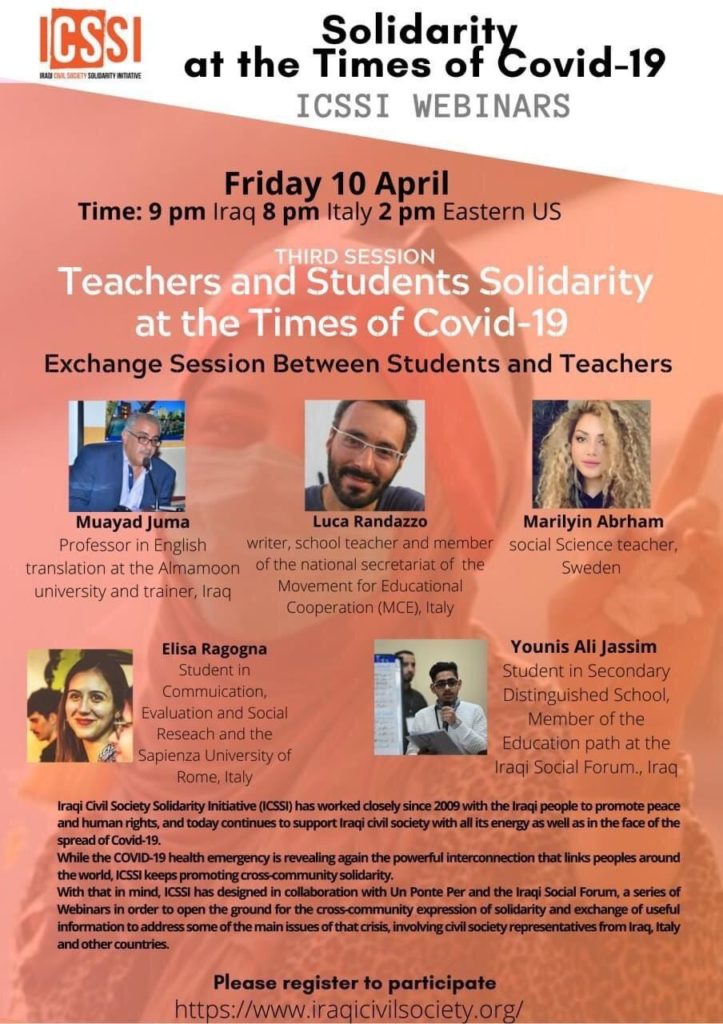

The teachers and students who helped us consider the current educational challenges and the future opportunities were:

- Muayad Juma a professor teaching English Translation at the Almamoon University in Baghdad, Iraq.

- Younis Ali Jassam a student at the Secondary Distinguished School in Baghdad, and a member of the Education path of the Iraqi Social Forum.

- Elisa Ragogna a student in Communication, Evaluation and Social Research at Sapienza University of Rome, Italy; she is also a member of the Students’ Association “Link”.

- Marilyn Abraham has been teaching social sciences to high school and middle school students in Sweden for over six years.

- Luca Randazzo teaches primary school in Italy; he is a member of the Italian movement for Educational Cooperation, the author many children’s books, and a social activist.

They first discussed how their nations are succeeding or failing to introduce new ways for teachers and students to interact during the COVID-19 pandemic.

New Education Techniques Adopted and Attempted in Iraq

Professor Juma extended hopes that all the participants were safe, wherever they were. He reported that prior to the epidemic in Iraq the Ministry of Higher Education had begun sponsoring workshops on a variety of Internet applications, such as Goggle Classroom, that were intended to support existing in-person classes. So when the Coronavirus appeared, university educators were partially prepared to make a transition to online education. However, some if not most, university students initially rejected the change. Too many do not have personal computers (although they do have cell phones) and most lack reliable Internet service. So, at first, university education effectively ceased because students did not participate. Recently professors began using applications that work on cell phones, and now a majority of students have joined. But there is a great deal of confusion; rumors persist that this year’s classes may not count, and there is uncertainty about how students can get credit for their work.

Younis Ali Jassam emphasized the big differences in the experiences of high school and university students. In his school, neither teachers nor students had any real experience with online education. And outside of the larger cities, like Baghdad, the challenges are even greater. Unlike the Ministry of Higher Education, the Ministry of Education, which is concerned with high schools and elementary schools, had not trained teachers on Internet applications; they were unfamiliar with the technology and how to use it. And, just to study is not enough; students are not getting the support and feedback learning requires. They are confused about whether the classes they take online will actually count. In addition, there are economic and cultural challenges. Students from poorer families and in rural areas are far more likely to have problems accessing online classes. Many parents forbid their daughters to have an online presence and so education of girls is likely to particularly suffer during the epidemic.

Experiences and Challenges in Italy and Sweden

Elisa Ragogna saw both similarities and differences in her experiences as a university student in Italy. While most families do have computers and cell phones, if there is more than one child in a family, they many not have access at the same time. Moreover, Internet access is not uniform and in some rural areas it is quite poor. Ms. Ragogna reported that she personally felt that her education was suffering from a lack of interaction, with her professors and her fellow students. Being online with 100 other students in an English class just does not allow for the questions and discussions that are possible in a lecture hall. Ms. Ragona’s mother, who teaches high school, described facing the same difficulties having genuine interactions with her students.

Marilyn Abraham began by saying how important and useful it was to hear about the variety of students’ and teachers’ experiences in different places. In Sweden, she reported, life was still pretty normal. The shops, restaurants and bars remain open. However, high schools and colleges have closed and transitioned to online classes. This was done in order to reduce the numbers of people using public transportation where it is very difficult to socially distance. Students all have laptops or iPads and are able to be online. Still it is difficult to maintain the same high levels of education and intellectual development without face-to-face interaction; some students choose not to attend. Additionally, students are no longer receiving other important support, like receiving healthy meals at school or psychological counseling for family problems like domestic violence or parental neglect. Right now, Abraham explained, the elementary schools and middle schools remain open, and function as they did before the pandemic.

Luca Randazzo shared some concerns that all education systems must consider as we educate students in the time of COVID-19. Randazzo’s primary focus is on the education of young students and he began by emphasizing four vital functions of traditional education in Italy:

- Educators connect through families concerning students’ individual needs, especially those who begin school with disadvantages, for example, those for whom Italian is not their first language, immigrants, and the poor.

- Motivation to study grows as a result of contact with peers and teachers; there is currently no clear replacement for this important source of motivation.

- Building knowledge and understanding not just a matter of acquiring facts and technical skills, is a shared, social exercise that requires engagement.

- School is a place to learn social skills, especially how democracy works, and what nonviolent engagement and conflict resolution requires. We must reinvest in social skills as soon as schools reopen.

While Mr. Randazzo clearly acknowledged the importance of protecting the health of students and their parents during the epidemic, he argued that these vital functions of face-to-face education should be reinstituted as soon as it is possible.

Common Themes Emerging From the Shared Experiences Concerning Education

Students face enormous challenges in adapting to online education. Professor Juma concurred that female students have special barriers—many do not want to post a photos of themselves online or make video presentations for a class; some use a fake name, often that of a male family member, which makes it is difficult for teachers to identify them. However, some female students have taken advantage of these challenges to develop new capacities in unexpected ways—sharing their work with friends and trading feedback. Increasingly many of Professor Juma’s students are being more resourceful about doing research and presentations. By comparison, Mr. Jassam said, Iraqi high school students and teachers had not successfully adapted to working online. Since we do not know how long the pandemic will continue, however, it is important to look forward and improve online education. The Ministry of Education needs to help high school and elementary teachers plan effective lessons and find ways to create more teacher-to-student, and student-to-student interaction.

The transition to online teaching presents particular difficulties for special needs students. Mr. Randazzo emphasized it is important to view special needs students as part of a larger group of disadvantaged students—the poor, those for whom Italian is not their first language, those who live with domestic violence or whose parents are absent—all factors making a child more likely to be left behind. Online education will begin next week for high school and elementary students in Italy. He emphasized how important it will be to keep everyone in touch. Online groups should be small—no m ore than four students—in order to allow for feedback. Some students will need individual calls. We need to give students concrete activities, using materials they have at home. In Sweden, students with special needs still have face-to-face education; they can still receive additional support if needed. Everyone is also getting information about hygiene and safety precautions. In Iraq, Professor Juma was not aware of any efforts to support special needs students.

Several participants pointed out that increased domestic violence was one of the impacts of the COVID-19 lockdowns. They stressed the need for providing parents and students with counseling and support. Ms. Ragogna said it was time to create new social networks to address social problems.

COVID-19 has created other problems for Italian university students, Ms. Ragogna added; these include difficulties in paying rent, taxes and tuition. Students are demanding that the government reschedule payments and provide financial aid. Access to books is also a challenge, one it is important to address before students take exams in June and July. She also emphasized that everyone is living through a social crisis; people are alone. Many students have volunteered to help others, for example, to shop for the elderly.

The webinar concluded with comments from participants, who expressed thanks for the opportunity to share information and experiences. Many students echoed concerns that a valuable component of education was lost without genuine interaction. Ms. Ragogna left everyone with a final thought—what we are doing it not a substitute for face-to-face interaction, but in confronting a crisis that as severe as COVID-19, we must try to take the best from what we must.