Four Scenes From Iraqi Reality

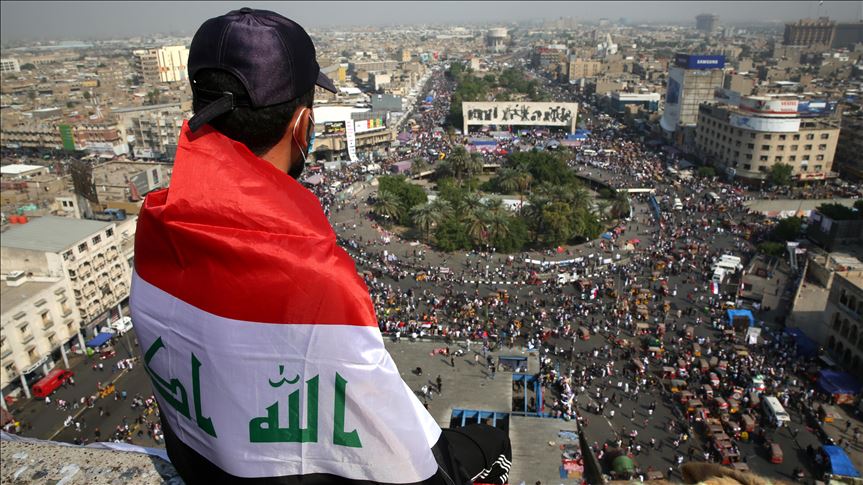

85 days, 485 martyrs, 19,000 wounded, 11 governorates galvanized to act, and the nonviolent protest movement in Iraq, known as the “October Revolution”, continues with its goal to change fundamentally the political system: to end financial and administrative corruption, to have a government that represents and respects Iraqi’s rich identity—not foreign interests, and to hold accountable all those who have killed peaceful protesters and those who have had a hand in suppressing their voices. To understand better the status of the October Revolution today, we consider here four scenes from the current political reality in Iraq that present the peaceful protestors’ shared framework and the challenges they are now confronting.

Scene One – Cautious Government Response and Failure to Address Protestors’ Demands

The political class has, since the start of the protests, expressed a variety of reactions to the protestors’ demands, ranging from skepticism and deceit, to rejecting any change, to finally making reluctant concessions when the pressure and influence of the protests mounted. This was most clearly evident in the acceptance of the resignation of the government of Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi. After that, Iraq entered a new phase of political uncertainty known as “the shape of the transition”. The protestors continued to demand fundamental change and reform, but the entrenched political parties refused to end their corrupt practices and so prevented necessary change. At present, the outcome remains uncertain.

After the former Prime Minister handed in his resignation to parliament on 1 December – which was viewed by the protestors as long overdue – the political battlefield began to boil as parties sought various strategies to preserve their power, influence and hegemony. According to Article 76 of the Iraqi Constitution: “The President of the Republic shall appoint a new candidate from the largest parliamentary bloc for the position of Prime Minister, provided that this candidate shall choose a government line-up, within a period not exceeding thirty days, to be presented to Parliament.”

Inside and outside the parliament, debates and deliberations raged as political parties sought to identify a new prime minister commensurate with their desire and ambition to shape the country’s future structure. However, the Sairoun Bloc—the largest parliamentary bloc—announced that it was waiving its right to nominate a prime minister and was leaving this decision to the nonviolent protesting masses and peaceful demonstrators in public squares throughout Iraq. The other large blocs were quick to search their ranks for individuals to succeed Abdul-Mahdi, but offered only names of unacceptable and largely corrupt candidates.

The protesters in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square and in the public squares in other Iraqi governorates refused to name a specific individual. Instead, they made a list of the criteria that a prime minister must meet. The most important of these are:

1 – That he is not a member of one of the current, powerful political parties or someone who held an official position in previous governments.

2 – That he is recognized for his integrity and acceptability by the Iraqi street; that his hands are not tarnished by corruption or other suspicions raised about him.

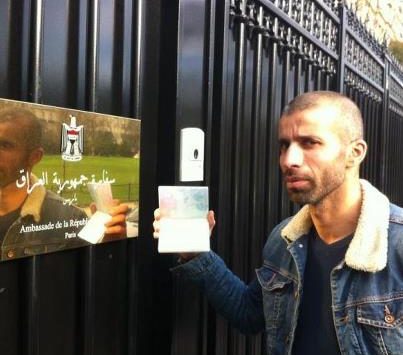

3 – That he must hold Iraqi nationality exclusively, and not be of dual nationality.

4 – That he agree to pave the way for early elections and withhold from participation in the nominations for the next electoral cycle.

120 deputies also signed a letter, delivered to President Barham Salih, that fully supported the above-mentioned conditions for the approval of a new prime minister. The supreme religious leadership in Najaf, in more than one sermon, called on the political blocs to comply with the requests from the nonviolent protesters, to end their procrastination and futile attempts to buy time.

The general consensus from the masses of peaceful protesters coalesced around choosing a prime minister who will perform the tasks of running a transitional government that can effectively oversee changes in the election law and the law of the High Elections Commission, and prepare for early elections to take place within 6 to 12 months. During this time, the current parliament would vote on the proposed reformed laws and subsequently dissolve itself.

However, the 15-day period stipulated by the Constitution in which to identify an acceptable candidate for the post of (transitional) Prime Minister ended on Thursday, 19 December. This failure has introduced great uncertainty on the political scene. All attention next turned to the parliamentary session on Sunday, 22 December, at which time the announcement of a candidate to fill this position was again expected. But once again, no Prime Minister was named, throwing Iraq into a state of existential ambiguity.

Since the parliament has been unable to agree on a candidate, it is likely that the President of the Republic, Mr. Barham Salih, will assume de facto Prime Minister duties for another 15 days, in accordance with Article 81 of the Iraqi Constitution. During that period, it is expected that he will appoint a candidate.

Scene Two – Repression, Intimidation, Threats and Assassinations

Away from the scene of parliamentary conflict, the resignation of Prime Minister Abdul-Mahdi produced an atmosphere of relative calm in the public squares where peaceful protesters gathered. Conflict between the nonviolent protesters and the anti-riot police and other security forces declined. Instances of the use of live bullets and tear gas against the demonstrators significantly decreased over the last two weeks, and the intensity of the confrontations between the two sides diminished to their lowest levels since the outbreak of the uprising on 1 October. Only occasional and minor sporadic confrontations arose.

On the other hand, this relative calm found no parallel peace in relations between political parties which grew bloodier and more tragic. Some political parties increased their targeting of activists and those supporting the protest movement. Militias affiliated with political parties also appeared to be playing a prominent role in this repression. The forms of targeting vary between direct and indirect threats, including an increase in kidnappings and forced abductions, and yet more brutal and senseless assassinations of activists and protesters.

Some of these incidents recalled days of insecurity and the chaos of armed conflict, with gangs once again taking up their old arms, like muffler pistols, sticky bombs and unmarked cars. Outside the squares where demonstrations occurred, the Iraqi security force and intelligence services intensified their campaign to pursue and arrest the largest possible number of those influential activists and human rights defenders who played a prominent role in the protest movement. These extrajudicial arrests, without any formal legal charges, are arbitrary and punitive, intended to intimidate their individuals and discourage continuation of the protests.

Scene Three – Revolutionary Stability and Steadfastness

With the onset of winter and falling temperatures, the housing and sit-in conditions in Tahrir Square and other public squares across Iraq have become more difficult; at night, temperatures drop significantly, leaving protesters in a severe and harsh environment. However, this reality has done little to affect the steadfast commitment of the protesters in the streets. On the contrary, the public squares have witnessed an increase in the number of tents, which have become a springboard for peaceful protest activities in the mornings and shelter for those seeking warmth at night.

In Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, young nonviolent protestors are working hard to enhance the civic-minded nature of their engagement. Hundreds of young women and men contribute daily to activities that range from cultural, to political and social education, to recreation. After campaigns to paint the sidewalks and the walls, to clean up the roads, and put lighting in the streets, the activists began building a space for physical and sporting activities on the banks of the Tigris River—including a volleyball field called “Tahrir Beach”. They also created the “Revolutionary Cinema” to screen short Iraqi films that portray a real sense of the movement, its background and guiding issues. A number of theaters were also established where revolutionary performances can be staged. In other Iraqi governorates similar activities aim to increase understanding of local issues and to support nonviolent protest activities.

Scene Four – Regional Intervention and the Need for Greater International Solidarity

With the escalation of events and their continuing accelerated pace, the role of regional powers—especially Iran—has emerged as an essential force on the Iraqi political scene. Without question, Iran stands at the top of the regional powers with influence. It has repeatedly interfered in events through its allied political parties and militias—all with the aim of blocking the peaceful protestors’ desired changes so as to preserve the Iran’s power over Iraqi politics under the previous government. Indeed, there are a number of militias, supported from outside Iraq, that are threatening and killing protestors and activists who oppose the current political system. The goal of these militias is to shut down the revolution.

Internationals commenting on the situation in Iraq have issued important appeals to stop the repression directed against the peaceful protesters. But those of us gathered in the public squares and on the streets need your understanding of the challenges we face and your deeper and sustained support of our demands.