What The War on Terror Looks Like: Iraq in The Eye

Synaps – Loulouwa al-Rachid & Peter Harling

The gap could not be greater between the war on the Daesh as it is narrated, on one side, and how it is experienced by ordinary people trapped in the crossfire, on the other. In Iraq, the story pushed by the various anti-Daesh protagonists is a consensual and simple one: as progress is made toward recapturing the city of Mosul, civilians held hostage by terrorists are freed; the former receive aid, while the latter are exterminated; and despite the hodgepodge of uncoordinated external forces, Iraqi troops and local militias, the unity of purpose created by Daesh is papering over potential divisions.

The reality is one where the most vulnerable Iraqis have almost no one to count on and virtually everyone to fear. Although their exact number is anyone’s guess, there are reportedly hundreds of thousands of civilians holed up in Mosul. No party to the campaign has enforced, or even discussed, a humanitarian corridor to facilitate their escape.

Harrowed by deprivations and hounded by Daesh, they flee whenever possible with whatever they can carry on foot; most head south, where little is done to greet them. Officials with the Ministry of Migration and Displaced, the institution formally in charge of handling internally displaced people, assess that 10 000 new arrivals occur daily. They also admit, in confidence, that the bulk of available resources are absorbed by intermediaries before reaching IDPs themselves. Camps are overcrowded and poorly equipped, even when it comes to basic sanitary facilities. Politicians nonetheless film themselves in company of the survivors, distributing token cash handouts in preparation for parliamentarian elections.

Most disturbing is the fear that is so palpable among the liberated. Iraqis fleeing Daesh do not leave their anxiety behind; they carry it with them, for more reasons than one. First is the erasure of any real distinction between fighters and civilians. Anti-Daesh forces treat Mosul as a killing-zone; negotiations over the fate of non-combatants are deemed unnecessary or unjustifiable. Tellingly, these actors have been claiming tens of thousands of dead terrorists, despite initially estimating Daesh’s numbers in the thousands.

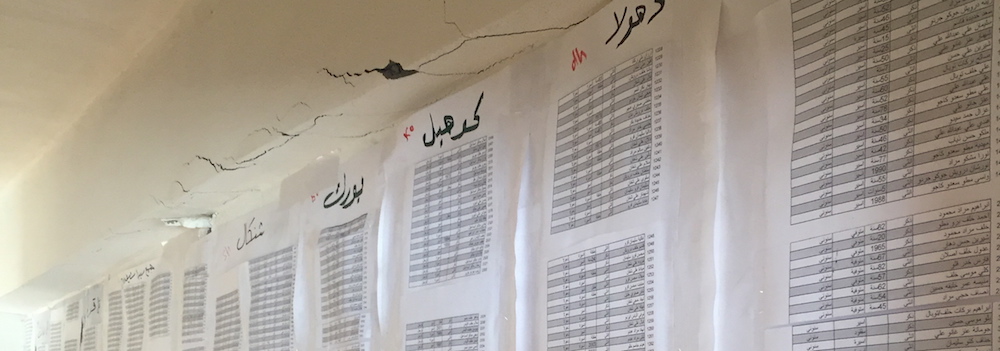

In the camps, people remain exposed to denunciation as members or sympathizers of the Jihadist movement, and may be arrested or disappear on the basis of what is less intelligence than gossip. Given that most subjects of Daesh were forced to accommodate it one way or another, the sword of Damocles is perpetually poised to strike. Civil servants, to get by, will have folded into Daesh’s expansive bureaucracy, which has left a paper trail engulfing much of society. Doctors will have treated its fighters. An elaborate and necessary economy of smugglers and traders will have done routine business with them. A former detainee in Daesh’s prison in Tall Afar said magnanimously: “just in that town you had some 3 000 people on the local police payroll. If we kill them all for being terrorists, who will be left?”

Random informants sell pictures of suspects for a mere 50 US dollars. Detention and interrogation conditions are predictably dismal. Having been tortured and racketed, many are then released, if only because holding on to them longer would interfere logistically with the raids. Others are paraded on television, where a string of disheveled analphabets forcefully confess world-class crimes.

Second, Daesh militants, with the exception of foreigners who gained disproportionate visibility, were mostly enmeshed within local society, making for very intimate forms of violence between people who are destined to remain neighbors. In an area of Iraq that had been neglected for decades, Daesh’s power grab translated into a cascade of smaller heists and petty score settling, subverting shaky hierarchies. The suppressed, the underdogs and the mediocre got a chance for advancement. Over the years, many have become “professionals of violence,” using every new crisis to promote themselves under one label or another.

One extreme case involved villagers of Yazidi faith, whose fertile land had for decades been coveted by Sunni Arabs settled in their vicinity; slaughtering and enslaving the former enabled the latter to extend their domain, far more than it served to establish some grand vision of a caliphate. “They became radical Salafists overnight and started calling us impure, just to lay hands on our property,” said a survivor. “Before that, they shared our meals and joined us in our celebrations—especially circumcision.”

Third, the liberated have few reasons to trust their saviors. Yazidis haven’t moved back to parts of Sinjar province retaken over two years ago. They are purportedly defended by a dozen militias who all speak in their name, but are divided between various external sponsors, compete over resources, and generally behave like warlords. Christians to the Northeast of Mosul are equally distrustful of their own plentiful paramilitary formations, who themselves root for a variety of Shiite and Kurdish militias.

The Shammar, a large, formerly unified Sunni Arab tribe in the adjacent Djazira, has split into several feuding factions each claiming ascendency. Many tribal armed groups dispatched to secure reclaimed territory boil down to two or three hundred men mounted on pick-up trucks, who busy themselves with the spoils of war—until they retreat precipitously at the first hint of a threat from Daesh.

But this is small fry, of course. As you move up the food chain, the bigger fish are equally menacing. Rival Kurdish militias backed by Turkey and the US are pushing their advantage, using every opportunity to extend their influence to areas deemed strategically important—located along the Syrian border, rich in oil or arable land, contiguous to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), or inhabited by minorities purportedly requiring “protection.”

Iranian-sponsored militias are part of the mix, using the presence of Shiite constituencies (notably segments of the Turkmen in Sinjar and Tall Afar and Shabak in Ninawa plains) to entrench themselves locally, and coopting Sunni warlords willing to sell out to anyone providing weapons and salaries. Whole villages have already been cleansed or bulldozed as part of this multipronged social reengineering of the region’s ethno-sectarian fabric, which promises vicious aftershocks.

What is left of an Iraqi “state” enjoys little recourse. Its various armed forces are not only disjointed, but compete among themselves for ammunition and battlefield prestige. Counterterrorism units, often in the lead, bitterly complain about their counterparts in the federal police, whom they accuse of indiscriminate violence. The latter feel betrayed by the former for providing support only reluctantly. Most troops and junior officers distrust their commanders, whom they see as obsessing about personal perks, media engagements and future political benefits derived from the sacrifice of ordinary infantrymen.

This chaotic security environment is made worse by the state’s failure to effectively exercise any of its sovereign prerogatives. Justice is mostly ad hoc, meted out by whomever takes over an area first. A corrupt and incompetent judiciary is ill-equipped to provide effective solutions to such an imbroglio of wrongdoings. For lack of any legal definition of slavery and sex-crimes, for instance, judges fall back on the all-encompassing category of “terrorism” to address the issue of Yazidi women captured and sold by Daesh. A judge confided that “the terrorists we arrest are scattered between competing and opaque authorities, not to mention foreign states. Victims of abuse, for their part, obsess about compensation, knock on innumerable doors and seek revenge by their own means.”

With the state’s security and judiciary functions in disarray, Baghdad could still restore some semblance of credibility by extending other basic services to the conflict’s many victims, in their direst moment of need. Here again, failure is near total. The Ministry of Health has hardly attempted to return to “liberated” areas, according to workers with an international medical NGO. Other essentials such as education and infrastructural rehabilitation remain similarly elusive, with no plan in sight to extend them systematically.

Meanwhile, displaced Iraqis—whose numbers reportedly total four million since turmoil swept over predominantly Sunni Arab regions in 2013—are increasingly prevented from seeking refuge where such services are available. Authorities forbid them from traveling without a guarantor or kafil, and frequently confiscate their ID cards to pin them down indefinitely in substandard “temporary” camps. Some governorates deport whole families that are loosely associated with Daesh—for instance through a relative accused of having joined the movement. Victims of violence are often denied indispensable paperwork such as birth or death certificates, on the assumption that they are somehow “sons of terrorists” and therefore warrant collective punishment.

With the government so thoroughly malfunctioning, Iraqi and international NGOs are left to shoulder much of the burden—yet these, too, leave much to be desired. Some local NGOs can be heard arguing in favor of keeping the “beneficiaries” of their work in places where life is obviously unsustainable. In the worst cases, this amounts to using Iraqis’ misery to fundraise for programs that ultimately do little to alleviate it.

A Yazidi survivor cried out: “our trauma is such that we should be helped to leave, not forced to stay. Our tormentors and rapists haven’t vanished. They and their families remain our neighbors. Those of us who managed to leave the country at least have some chance to heal.” Worse, a cynical business has developed around captive Yazidi women, who are sold by Daesh fighters to NGOs for rates that have climbed up to 50 000 dollars, in a market where intermediaries take cuts for negotiating their salvation.

International actors are themselves of limited succor, their capacities hemmed in by waning attention and meager resources. The reductive narrative presenting the war on terror through the lens of valorous Iraqi soldiers saving civilians from Daesh has minimized public interest in the real human costs of this spectacular bloodletting. Fatigue with years of byzantine conflict, the Syrian tragedy, US politics and the EU’s expected meltdown collectively relegate Iraq to the status of afterthought.

What resources are available are diluted by the usual scattering of efforts across numerous, uncoordinated programs that seem to touch shallowly on everything while ultimately satisfying none of the countless needs. This patchwork is managed by a diverse array of organizations all setting their own priorities, which run the gamut from preserving heritage sites, rehabilitating infrastructure, demining, psychological support, minority rights, mediation and reconciliation, through to LGBT protection and international criminal law. What may seem, on the face of it, like a holistic approach to a multifaceted crisis turns out, in practice, to look like a Greek fable of old: a circle of hell where the suffering receive every good on earth in such trivial quantities as to pique their pain.

Clausewitz famously described war as the continuation of politics by other means. Iraq, however, challenges this definition, given the triumph of petty short-termism over any coherent political endgame. All players involved seem to be wagering that their own shortcomings will somehow be offset by their equally inadequate partners. The international coalition trumpets tactical victories despite lacking any coherent long-term strategy, leveling neighborhoods and villages in support of unruly militias; it acts, in the meantime, as though the Iraqi government might somehow reform itself and reconcile with its detractors, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Baghdad appears to bank on Daesh to justify all its failings, on foreign military aid to defeat the terrorists, on uncontrollable militias and tribes to hold the ground, on a weak and chaotic “civil society” to mend the social fabric, and on the outside world to rebuild from the rubble. For their part, Turkey, Iran and the KRG are pushing their pawns as if a thoroughly dislocated, brutalized society would miraculously settle enough to endorse their opportunistic gains—when they are merely sowing the seeds of the next rounds of fighting.

In this Hobbesian dystopia where politics has vanished, ordinary Iraqis do not fear terrorists as much as they are terrorized by everyone. They are utterly defenseless—forsaken by their purported leaders, preyed upon by their liberators, ignored by the rest of the world. Perhaps the worst part of their plight is how difficult it is for them to imagine any sort of future. For they know firsthand that, in today’s Iraq, war is just the continuation of war by other means.