Painful Career Path for Women Journalists

Sabreen Kadhum

There is substantial evidence pointing to the fact that women working in visual, audio or print media are exposed to malicious harassment which offenders claim provides them some protection from this harassment, but is in fact a form of opportunistic and soft extortion.

Unfortunately, no one wants to talk about this widespread and discriminatory issue because it is seen as disgraceful and shameful. The end result is that many women journalists in the country suffer abuse and yet fail to get the attention and support they need and deserve, and those who are responsible for the harassment are rarely brought to justice.

A woman in the media begins her career by receiving offers from men already working in the field. Her start is dependent on their recognition and perception of her character and reputation.

The Iraqi Women’s Journalist Forum did a study on the harassment of women in the workplace and had to declare in a statement to all those who participated that they would remain anonymous, that no names would be written on copies of completed questionnaires. This reflects the shame associated with harassment.

According to this study, 68% of women journalists in Iraq are exposed to sexual harassment at work and on the street.

The study adds that only 1% of women journalists are in management positions, and 80% of them suffer from career discrimination.

Liberally oriented media institutions may seem to women to be simply another version of religious institution, that is, as controlled by parties and politically motivated interest groups, lacking professionalism and with no regard for proper behavior. Women in media — whether liberal or conservative — have not been given genuine opportunities to work, rather they are often required to spend long hours sitting in make-up rooms. This reinforces the prevalent belief that views women as capable of being stylish, but certainly not skilled enough to write news or edit reports, or develop sophisticated language and diction. Again and again we find that news related to politics and security is reported by men, while society and culture pieces are covered by women.

Do women really cannot cover the war?

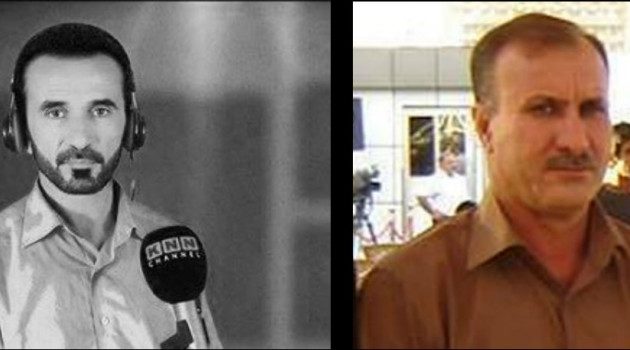

I recall here the words of the deceased female journalist, Atwar Bahjat: women in the media, she said, work 10 times as hard as men, yet receive 1/10 the recognition and respect within their respective institutions. Atwar was killed by Al-Qaeda when she was on her way to cover the bombing of the Dome of Al-Askari in Samarra, and if she hadn’t been working for a prominent media institution like Al-Arabiya, she would likely not have been honored after her death for the tremendous courage she displayed.

My attention was recently drawn to the awards given by the Iraqi Journalists Syndicate to workers in media who cover events in the provinces fighting against Daesh. I did not find a single woman among about hundred or more names. I wonder why, given the numbers of Iraqi women journalists available, none was given the opportunity to go to the trouble spots, while foreign women journalists were able to carry out fantastic coverage with support from their institutions?

I was recently assigned by a media institution to supervise training for two girls from the Media School in Baghdad. One never showed up, and when I asked the other about her reasons for wanting to work in the media, she said: fame. I told her that this work is for those who do not want to depend on their sect identity (i.e., as a journalist, one is no longer defined primarily as being Sunni or Shiite), and though the road to becoming a journalist is neither short nor easy, with hard work and dedicated study, it is possible.

Two days later, I saw her with a man working in media. She had used him to get a position and reach her career goals. She avoided me — or more specifically, she avoided the one who challenged and pushed her, and instead went to the one who would make her laugh, who would make her life easy. Ultimately, she took the path of her absent friend.

The journalist Rima Maktabi once said in an interview for one of the agencies: women are the first victims of war, and they are the most able to cover it. I recall an interview with the deceased journalist Ahmad Muhanna when he headed Al-Alam newspaper, in it he said that the war in Iraq will not end unless women confront it through their own words and pointed insights, because war leaders are clever, and women are like them.

Muhanna knows just like I know that if Rima Maktabi worked in an Iraqi institution, she would be doomed, but surely, Maktabi too has had her struggles to reach her position.