Underage and Trapped: Female Iraqi Factory Workers Need Help

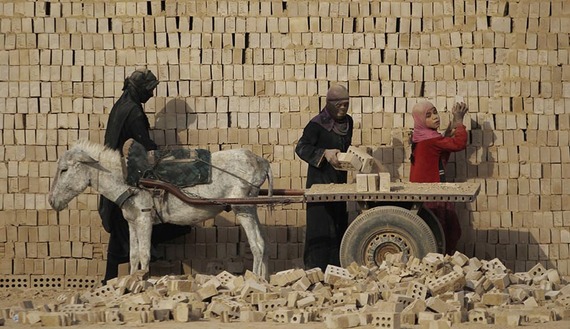

BABIL, Iraq — Shayma Hassan, 16, walks 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) each day to the brick factory in Bahr al-Najaf in the city of Najaf, 161 kilometers (100 miles) south of Baghdad. Her hectic work day starts at 6 a.m. and ends at 5 p.m.

Along with four other women, Shayma moves bricks out of molds and into and out of the oven. For all this hard work, she gets paid $7 per day.

“I never went to school because I live in the village and I need to make money. My only hope now is to have my own family, since my mother decided that I should get married,” she told Al-Monitor.

Even when she’s ill, Shayma has to work in this polluted environment to put food on the table, especially since her mother, who used to work in the same factory, is sick and can only take care of some plants around the house.

Shayma’s employer Abu Haidar, who preferred not to give his full name, told Al-Monitor, while Shayma timidly stared at the floor, “The women here work with dignity and I help them with their living expenses.” However, Abu Haidar added, “The wage is minimal, but most of the brick factories are no longer as profitable as they were before.”

Many girls who work are violating the Iraqi labor law. For instance, the girls who work in the plastic waste recycling factories in the city of al-Mahawil, north of Hillah in the center of Babil province (100 kilometers, or 62 miles, south of Baghdad) are not 16 yet. The labor law prohibits minors from working and stipulates that education is mandatory up to age 16. In these factories, young girls work tirelessly on assorting garbage before putting it into thermal and plastic cutting machines for recycling.

Saad al-Heli, the owner of a plastic waste recycling factory, told Al-Monitor, “Girls are more suitable [for this work] than boys, since they are more compliant.“

Fatimah, 16, told Al-Monitor, as she cleaned her face and hair from the plastic ooze coming from the machine, “I get paid $5 for about 6 hours of work.”

As all other girls there, Fatimah comes from a poor family and has never been to school. However, she prefers to work in this female-only factory, because she was a victim of sexual assault when she worked in a factory with men.

Fatimah refused to give details concerning the incident and she simply commented, “Working with men is risky,” referring to the incident.

This is probably why Heli does not hire boys to work with the girls in his factory. “They created many problems and the police had to interfere,” he said. But he seems fine with hiring underage girls, saying, “There is no real supervision and I make sure to treat them like my own daughters.”

Ghofran Majed, a local feminist activist, told Al-Monitor in the town of Babil: “Hiring uneducated young girls has serious social repercussions. … Field studies show that many working girls become victims of oppression and sexual harassment, which delays their marriage. Most of these young girls come from poor families that allow them to work because they need the money.”

Ferial Mhamdawi, 15, has been working in factories since she was a child. She got married at a very young age, probably two or three years ago (parents in these regions of Iraq marry their daughters off at age 11 or 12), but is now divorced and back at work.

“The biggest mistake of my life was not attending school,” she said. She married a man 20 years her senior who accused her of being involved with another man, which led to their divorce.

In general, girls often become the victim of rumors that affects their reputation, according to social researcher Sakinah Daoud, who told Al-Monitor, “The future of young working girls remains uncertain until they get married. In case they do not, they risk [getting involved] in prostitution and the sex trade.”

Suheila Abbas, a member of the council of Babil, told Al-Monitor: “The solution to this phenomenon is to create a social protection network, which prevents child labor as well as the labor of young girls, in addition to establishing laws that penalize illegal employment.”

This first step, Abbas said, “Is to create job opportunities under the auspices of the government, while simultaneously launching civil society initiatives to provide medical care and proper education for all segments of society, especially women and children who are forced to work.”