Women in Iraq Defiantly Take to the Streets Despite Fears they ‘Could Die at Any Moment’

Female activists speak in Baghdad about why there are more women protesting than ever before

Pesha Magid – Independent

As Saba al-Mahdawi left Baghdad’s Tahrir Square after a long day of helping protesters on the frontlines, the teargas started to take its toll. Choking, she was brought back to her friend’s tent. They told her to go home – she had done enough for the day.

But she never made it. Just a few hours later, she was kidnapped by unknown men as she got into her car. For two weeks her face circulated on social media and the hashtag: “Where is Saba?” went viral.

“We are all here threatened. Saba wasn’t famous, she was just someone who loved Iraq and was here, and that means that anyone could be kidnapped,” says Haneen Ghranem, 27, an activist and protester.

“There are many women here. All the women who came out from the beginning, before and after the kidnapping of Saba are still here. All know they could face kidnapping,” says Ghranem.

She works at a grassroots radio station, in an abandoned building in Tahrir square that has become a makeshift centre for protesters determined to make women’s voices heard.

“All the women here know that they could die at any moment,” she adds.

She’s not alone in hoping to inspire more women to go to the square.

Rua Khalaf, 31, was one of the few women present at the very beginning of the protests on 1 October when snipers used live rounds to fire directly on demonstrators in the streets.

“Saba became a symbol of the brave women and of the conscious young people,” Mohamed Fadhel, a civil activist and friend of Mahdawi’s, tells The Independent.

“The kidnappings, tortures, and deaths that are intended to scare us will do nothing except increase our presence here until we finish with this failed and corrupt government.”

Mahdawi was released earlier this month, but her experience has left an indelible mark on the square as she has become a symbol of the rising presence of female protesters in Iraq’s streets: threatened, facing great personal risk, but determined all the same.

“I wanted to go so it would be remembered that women were there,” she says.

She has been participating in protests since 2015, and says that earlier protests did not have the same representation of women as they do now.

The marches paused in mid-October during the holy Shia pilgrimage of Arbaeen, but when they resumed women began to attend in numbers previously unseen in Iraqi protests.

On 25 October, Khalaf wore an Iraqi flag wrapped close around her shoulders, and her face turned against the drifting teargas.

Her friend snapped a photo of her profile and posted it online – and suddenly her face was everywhere.

She goes to the square daily, coordinating food and medical support for the protesters and says she is often recognised on the street.

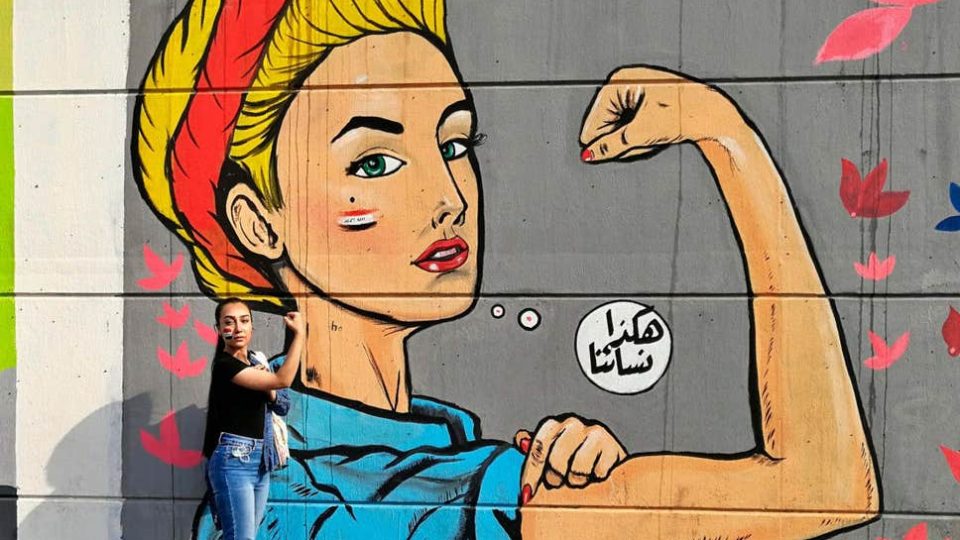

Now Khalaf’s face, like Mahdawi’s, has become iconic within Tahrir Square. Graffiti artists plan to paint a portrait of her on a wide wall in the Saadoun underpass leading to Tahrir Square, now an informal gallery of revolutionary art.

“The participation of women in the protests broke the barriers between men and women; it changed the typical view of women that they stay away from taking part in politics,” she says.

Another protester, Nour Faisal, 22, says women are feeling more empowered by coming to the demonstrations.

“On 1 October when I went [to the protests], I was wearing heels. They were shooting and I was running, it was hard to run, but I wore it as a type of protest. I took a photo of my heels and wrote that Iraqi women’s heels are straighter than our government,” she says.

Faisal wants to emphasise that femininity can mean strength, and has a place at the heart of the square.

“The woman is there, the women with her beauty and style is going there and can do things,” she adds.

She’s not alone in that effort.

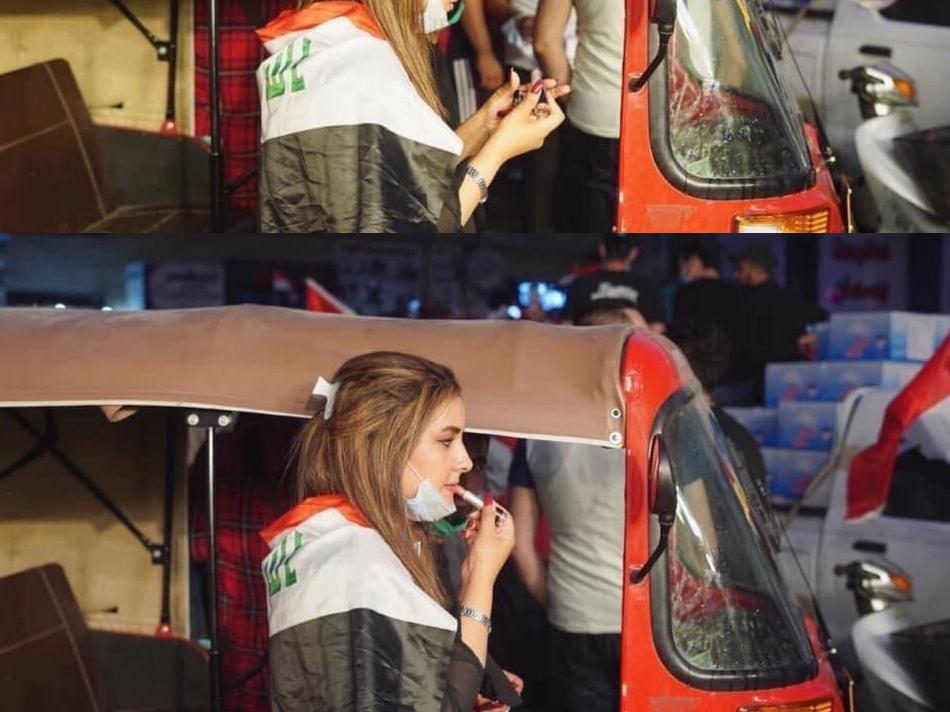

Refal al-Aziz, 26, a protester and journalist, made a point to publish a picture of herself putting on red lipstick in the mirror of a tuk-tuk.

The picture went viral, getting shared across social media and published on TV.

“I wanted to publish this picture to represent this magnificent participation of women. I thought the thing that represents femininity worldwide is red lipstick… and the thing that symbolises the protests is the tuk-tuk,” Aziz says.

The humble three-wheeled vehicle has become famous in the protest for nimbly wheeling to the most dangerous areas and rescuing the injured. “Women and tuk-tuks, no one expected they would be there with such strength!” Aziz continues.

“Many thought that Iraqi women were weak but the protests proved the opposite. There are female doctors and volunteers [in front of the security forces] facing live bullets and teargas canisters – and they are not afraid.”